About this Release

- Eduard Abramian

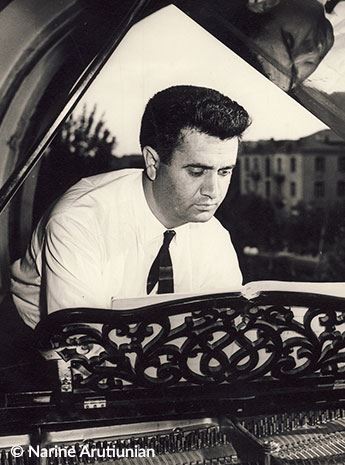

- Alexander Arutiunian

- Louis Aubert

- Arno Harutyuni Babadjanian

- Eduard Bagdasarian

- Mily Alexeyevich Balakirev

- Georges Baz

- Ludwig van Beethoven

- Lars Aksel Bisgaard

- York Bowen

- Ferruccio Busoni

- Teresa Carreño

- Johann Baptist Cramer

- Tanya Ekanayaka

- George Enescu

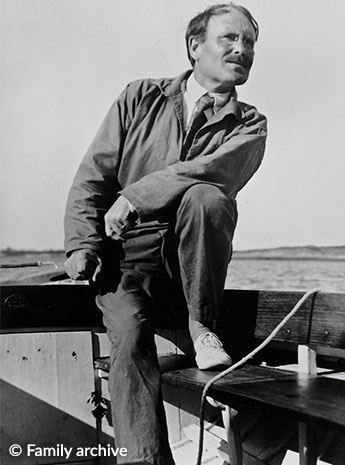

- Helge Evju

- Ignaz Friedman

- Gerhard Frommel

- Anis Fuleihan

- Boghos Gelalian

- George Gershwin

- Philip Glass

- Mikhail Ivanovich Glinka

- Benjamin Godard

- Louis Theodore Gouvy

- Percy Grainger

- Edvard Grieg

- Philip Hammond

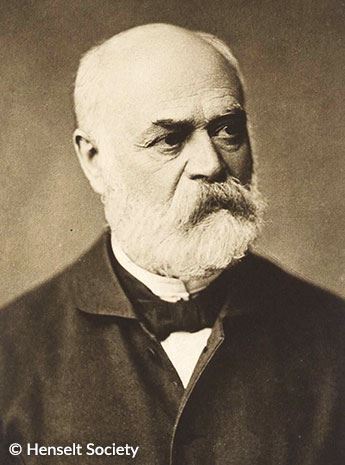

- Adolf von Henselt

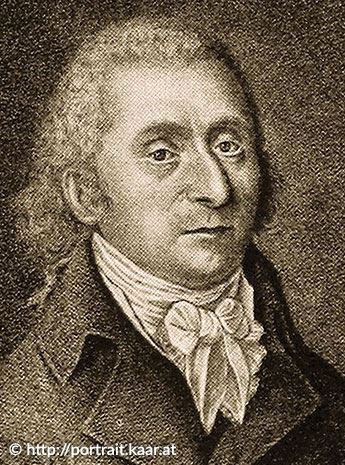

- Franz Anton Hoffmeister

- Józef Hofmann

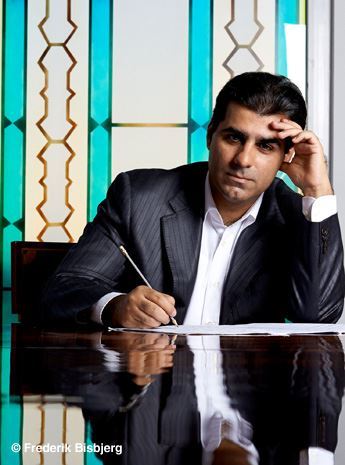

- Afshin Jaberi

- Vítězslava Kaprálová

- Murad Kazhlayev

- Aram Il'yich Khachaturian

- Houtaf Khoury

- Komitas Vardapet

- Leopold Koželuch

- Johan Kvandal

- Paul Le Flem

- Arthur Lourié

- Finn Lykkebo

- Ivo Maček

- Nicolai Medtner

- Alexander Mosolov

- Christian Gottlob Neefe

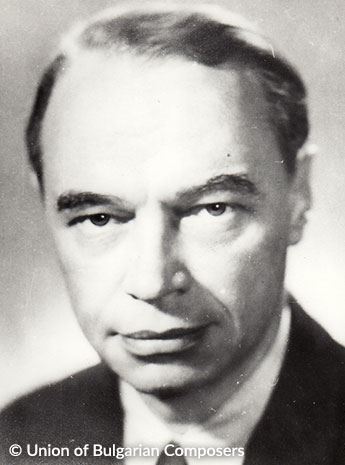

- Dimitar Nenov

- Walter Rudolph Niemann

- Per Nørgård

- Henrique Oswald

- Manuel María Ponce

- Jaan Rääts

- Joachim Raff

- Andre Riotte

- Jean Roger-Ducasse

- Nikolay Andreyevich Roslavets

- Camille Saint-Saëns

- Gustave Samazeuilh

- Erik Satie

- Florent Schmitt

- Erwin Schulhoff

- Valentin Silvestrov

- Martial Solal

- Toufic Succar

- Maria Szymanowska

- Boris Tchaikovsky

- Alexander Tcherepnin

- Daniel Gottlob Türk

- Johann Baptist Vaňhal

- José Vianna da Motta

- Jan Hugo Voříšek

- Mieczysław Weinberg

GRAND PIANO: THE KEY COLLECTION

Three Centuries of Rare Keyboard Gems

The Grand Piano label is dedicated to exploring undiscovered piano repertoire by unfamiliar composers, producing high quality, often world première recordings, performed by virtuoso authorities in their chosen field. Marking the label’s 5th anniversary, this collection is a comprehensive guide through the history of keyboard music from the invention of the fortepiano to today’s living composers, as well as taking the listener on a musical adventure through a geographically global range of rare musical gems, with all of their new and exciting sounds and fresh perspectives.

Tracklist

|

Neefe, Christian Gottlob

|

|

1

12 Keyboard Sonatas (1773): Sonata No. 4 in C Minor: III. Presto (1773) (00:02:25)

|

|

Türk, Daniel Gottlob

|

|

2

12 Keyboard Sonatas, Collection 2 (1777): Sonata No. 2 in E-Flat Major: II. Adagio assai (1777) (00:02:53)

|

|

Koželuch, Leopold

|

|

3

Piano Sonata in E-Flat Major, Op. 10, No. 1, P. XII:15: III. Allegretto () (00:04:13)

|

|

Vaňhal, Johann Baptist

|

|

4

3 Neue Caprice-Sonaten, Op. 31: No. 2 in G Minor, "Amoroso": III. Allegretto () (00:03:32)

|

|

Hoffmeister, Franz Anton

|

|

5

Keyboard Sonata in A Major (1790): III. Presto () (00:03:31)

|

|

Beethoven, Ludwig van

|

|

6

Sonata for Piano 4 Hands in D Major, Op. 6: II. Rondo: Moderato (1797) (00:03:23)

|

|

Cramer, Johann Baptist

|

|

7

Studio per il pianoforte, Book 1, Op. 30: No. 26 in G-Sharp Minor (1804) (00:02:07)

|

|

Busoni, Ferruccio

|

|

8

Klavierübung in 10 Books, Book 7: 8 Etudes after Cramer: No. 5 in C Major (1922) (00:02:02)

|

|

Szymanowska, Maria

|

|

9

18 Danses: No. 7. Valse in B-Flat Major () (00:01:31)

|

|

Voříšek, Jan Hugo

|

|

10

Piano Sonata in B-Flat Minor, Op. 20, "Quasi una fantasia": III. Finale: Allegro con brio (1824) (00:04:12)

|

|

Glinka, Mikhail Ivanovich

|

|

11

Variations on the song Sredi dolinï rovnïye in A Minor (Among the Gentle Valleys) (1826) (00:03:01)

|

|

Henselt, Adolf von

|

|

12

12 Études caractéristiques, Op. 2: No. 6 in F-Sharp Major, "Si oiseau j'étais, à toi je volerais!" () (00:02:03)

|

|

Saint-Saëns, Camille

|

|

13

6 Bagatelles, Op. 3: Bagatelle No. 3: Poco adagio (1855) (00:03:00)

|

|

Balakirev, Mily Alexeyevich

|

|

14

Piano Sonata in B-Flat Minor, Op. 3, "Grande Sonate": IV. Finale: Allegro grazioso () (00:06:20)

|

|

Raff, Joachim

|

|

15

Fantaisie-polonaise, Op. 106 (1861) (00:06:58)

|

|

Gouvy, Louis Theodore

|

|

16

Sonata for Piano 4 Hands in C Minor, Op. 49: III. Minuetto: Moderato (1869) (00:04:16)

|

|

Carreño, Teresa

|

|

17

Souvenirs de mon pays, Op. 10 () (00:07:14)

|

|

Grieg, Edvard

|

|

18

Piano Concerto in B Minor (fragments) (1883) (00:02:34)

|

|

Evju, Helge

|

|

19

Piano Concerto in B Minor: V. Finale (on fragments by E. Grieg) () (00:04:17)

|

|

Godard, Benjamin

|

|

20

Promenade en Mer, Op. 86 () (00:03:24)

|

|

Satie, Erik

|

|

21

Allegro (1884) (1884) (00:00:29)

|

|

Hofmann, Józef

|

|

22

Mazurka in B Minor (1885) (00:02:11)

|

|

Vianna da Motta, José

|

|

23

Cenas Portuguesas, Op. 9: No. 2. Chula (1893) (00:03:22)

|

|

Fauré, Gabriel

|

|

1

Dolly, Op. 56: No. 1. Berceuse: Allegretto moderato (arr. A Cortot for piano) (1896) (00:02:30)

|

|

Roger-Ducasse, Jean

|

|

2

6 Préludes: No. 2. Très calme (1907) (00:01:38)

|

|

Samazeuilh, Gustave

|

|

3

Piano Suite in G Minor: II. Française (1902) (00:02:54)

|

|

Medtner, Nicolai

|

|

4

Piano Sonata in F Minor, Op. 5: II. Intermezzo: Allegro (1903) (00:03:44)

|

|

Le Flem, Paul

|

|

5

Le chant des genêts: No. 4. Pour bercer (1910) (00:02:30)

|

|

Schmitt, Florent

|

|

6

Feuillets de voyage, Book 2, Op. 26: No. 2. Mazurka (1913) (00:01:32)

|

|

Ponce, Manuel María

|

|

7

Barcarola mexicana, "Xochimilco" (1915) (00:02:39)

|

|

Friedman, Ignaz

|

|

8

4 Preludes, Op. 61: No. 1. Pensieroso (1915) (00:01:46)

|

|

Enescu, George

|

|

9

Pièces impromptues, Op. 18, "Suite No. 3": I. Mélodie (1916) (00:03:16)

|

|

Komitas Vardapet

|

|

10

7 Folk Dances: No. 5. Shushiki of Vagharshapat () (00:03:34)

|

|

Tcherepnin, Alexander

|

|

11

10 Bagatelles, Op. 5: No. 6. Allegro con spirito (1918) (00:01:05)

|

|

Niemann, Walter Rudolph

|

|

12

3 Compositions for Piano, Op. 7: No. 3. Arabeske: Vivace e leggiero () (00:01:41)

|

|

Schulhoff, Erwin

|

|

13

5 Pittoresken, Op. 31: No. 1. Foxtrott (1921) (00:02:36)

|

|

Roslavets, Nikolay Andreyevich

|

|

14

5 Preludes: Prelude No. 4 (1922) (00:01:42)

|

|

Oswald, Henrique

|

|

15

Album, Op. 33: No. 2. Idylle (c. 1920) (00:02:03)

|

|

Gershwin, George

|

|

16

Rhapsody in Blue: Andantino moderato (version for piano) (1924) (00:02:30)

|

|

Khachaturian, Aram Il'yich

|

|

17

2 Pieces: No. 1. Waltz-Caprice (1926) (00:02:21)

|

|

Lourié, Arthur

|

|

18

Petite Suite in F Major: II. — (1924) (00:01:12)

|

|

Mosolov, Alexander

|

|

19

Turkmenian Nights: III. Allegro (1929) (00:02:21)

|

|

Aubert, Louis

|

|

20

Feuille d'Images: No. 2. Chanson de route: Avec entrain (1930) (00:02:16)

|

|

Nenov, Dimitar

|

|

21

Etude No. 1 (1932) (00:01:35)

|

|

Frommel, Gerhard

|

|

22

Piano Sonata No. 2 in F Major, Op. 10: III. Allegro (1935) (00:04:41)

|

|

Kaprálová, Vítězslava

|

|

23

Grotesque Passacaglia (1935) (00:02:34)

|

|

Grainger, Percy

|

|

24

Lincolnshire Posy: IV. The Brisk Young Sailor (version for 2 pianos) (1937) (00:01:46)

|

|

Bowen, York

|

|

25

24 Preludes, Op. 102: Prelude No. 4 in C-Sharp Minor: Allegro con fuoco (1938) (00:01:36)

|

|

Kvandal, Johan

|

|

26

Lyric Pieces, Op. 5, Nos. 4-7: No. 7. Scherzino: Allegro scherzando (1946) (00:02:14)

|

|

Succar, Toufic

|

|

27

Variations sur un theme oriental () (00:06:18)

|

|

Nørgård, Per

|

|

28

Toccata (1949): Fuga (1949) (00:02:33)

|

|

Weinberg, Mieczysław

|

|

29

Piano Sonatina, Op. 49: I. Allegro leggiero (1951) (00:02:20)

|

|

Kazhlayev, Murad

|

|

1

Picture Pieces: No. 2. Welcome Overture (1971) (00:02:59)

|

|

Abramian, Eduard

|

|

2

24 Preludes: No. 1 in E-Flat Major (1972) (00:01:22)

|

|

Bagdasarian, Eduard

|

|

3

24 Preludes: No. 3 in G Major (1958) (00:00:40)

|

|

Baz, Georges

|

|

4

Esquisses: VII. Une soirée libanaise () (00:02:07)

|

|

Arutiunian, Alexander

|

|

5

3 Musical Pictures: No. 3. Sassoun Dance (1960) (00:02:30)

|

|

Babadjanian, Arno Harutyuni

|

|

6

6 Kartin (6 Pictures): No. 3. Toccatina (1965) (00:01:53)

|

|

Gelalian, Boghos

|

|

7

Tre Cicli: III. Allegro con furia (1969) (00:02:46)

|

|

Rääts, Jaan

|

|

8

Piano Sonata No. 4, Op. 36, "Quasi Beatles": II. — (1969) (00:02:31)

|

|

Glass, Philip

|

|

9

Music in Fifths (1969) (00:05:47)

|

|

Fuleihan, Anis

|

|

10

Piano Sonata No. 9: IV. Presto (1970) (00:03:45)

|

|

Tchaikovsky, Boris

|

|

11

Sonata for 2 Pianos: III. Etude (1973) (00:02:50)

|

|

Lykkebo, Finn

|

|

12

Tableaux: No. 1. Couleurs et valses: Alla cadenza. Allegretto. Lento a la valse (1979) (00:02:10)

|

|

Solal, Martial

|

|

13

Voyage en Anatolie (Journey to Anatolia) () (00:05:34)

|

|

Bisgaard, Lars Aksel

|

|

14

Barcarole (1987) (00:03:14)

|

|

Maček, Ivo

|

|

15

Prelude and Toccata: Toccata (1987) (00:02:51)

|

|

Riotte, Andre

|

|

16

Météorite et ses métamorphoses: Métamorphose II: En oppositions (2001) (00:01:25)

|

|

Silvestrov, Valentin

|

|

17

2 Waltzes, Op. 153: No. 2. Allegretto (2009) (00:02:31)

|

|

Hammond, Philip

|

|

18

Miniatures and Modulations: Open The Door Softly (2011) (00:02:24)

|

|

Khoury, Houtaf

|

|

19

Piano Sonata No. 3, "Pour un instant perdu…": III. Quête () (00:06:17)

|

|

Ekanayaka, Tanya

|

|

20

Adahas: Of Wings Of Roots (2010) (00:04:18)

|

|

Jaberi, Afshin

|

|

21

Piano Sonata No. 1, "The Seeker": I. Allegro (2011) (00:06:08)

|

|

Glass, Philip

|

|

22

The Hours: Choosing Life (arr. M. Riesman and N. Muhly for piano) (2002) (00:03:48)

|

The Composer(s)

Among those who worked principally in Armenia, without seeking to establish any worldwide reputation, the composer, pianist and teacher Eduard Aslanovich Abramian was one of the most significant and respected: a key figure in the modern development of Armenian music.

Among those who worked principally in Armenia, without seeking to establish any worldwide reputation, the composer, pianist and teacher Eduard Aslanovich Abramian was one of the most significant and respected: a key figure in the modern development of Armenian music.  A member of the so-called Armenian “Mighty Handful” (along with Arno Babadjanian, Edward Mirzoyan, Adam Khudoyan and Lazar Saryan), he was awarded numerous Soviet state prizes, including the Stalin Prize (1949), People’s Artist of Armenia (1962), People’s Artist of the USSR (1970) and Honoured Citizen of Yerevan (1987). His music has been performed by many distinguished musicians, from Yevgeny Mravinsky and Valery Gergiev, to Sergey Khachatryan, Ilya Grubert and Jack Liebeck. Arutiunian died on 28 March 2012.

A member of the so-called Armenian “Mighty Handful” (along with Arno Babadjanian, Edward Mirzoyan, Adam Khudoyan and Lazar Saryan), he was awarded numerous Soviet state prizes, including the Stalin Prize (1949), People’s Artist of Armenia (1962), People’s Artist of the USSR (1970) and Honoured Citizen of Yerevan (1987). His music has been performed by many distinguished musicians, from Yevgeny Mravinsky and Valery Gergiev, to Sergey Khachatryan, Ilya Grubert and Jack Liebeck. Arutiunian died on 28 March 2012.  Louis Aubert, like his contemporaries Joseph Guy Ropartz (1865–1955) and Paul Le Flem (1881–1984), was of Breton origins: he was born on 19th February in Paramé, today part of Saint-Malo. Even as a child Aubert had an excellent ear for music—he was a gifted pianist and sang as a treble chorister in the main churches of Paris. His talents were noted by one of his first teachers, Charles Steiger, who soon brought him to the attention of Albert Lavignac, a professor at the Paris Conservatoire. Aubert went on to study harmony with Lavignac, discovering the great composers in the history of music along the way. He also studied piano with Antoine-François Marmontel and, later, Louis Diémer. Aubert had begun studying composition with Fauré in 1893, and by 1896 his fellow students also included Maurice Ravel, Florent Schmitt, George Enescu, Charles Koechlin, Jean Roger-Ducasse, Paul Ladmirault and Émile Vuillermoz.

Louis Aubert, like his contemporaries Joseph Guy Ropartz (1865–1955) and Paul Le Flem (1881–1984), was of Breton origins: he was born on 19th February in Paramé, today part of Saint-Malo. Even as a child Aubert had an excellent ear for music—he was a gifted pianist and sang as a treble chorister in the main churches of Paris. His talents were noted by one of his first teachers, Charles Steiger, who soon brought him to the attention of Albert Lavignac, a professor at the Paris Conservatoire. Aubert went on to study harmony with Lavignac, discovering the great composers in the history of music along the way. He also studied piano with Antoine-François Marmontel and, later, Louis Diémer. Aubert had begun studying composition with Fauré in 1893, and by 1896 his fellow students also included Maurice Ravel, Florent Schmitt, George Enescu, Charles Koechlin, Jean Roger-Ducasse, Paul Ladmirault and Émile Vuillermoz.  Babadjanian spent much of his time teaching and giving concerts. His extraordinary Piano Trio was competed in 1952 and was followed in 1954 by his orchestral Poem-Rhapsody. The Sonata for Violin and Piano was produced in 1959, followed by the Cello Concerto, which was written for and dedicated to Mstislav Rostropovich. Among his last compositions were the Six Pictures for Piano (1965), the Third String Quartet (1979) and the Nocturne for piano and symphonic jazz ensemble (1981).

Babadjanian spent much of his time teaching and giving concerts. His extraordinary Piano Trio was competed in 1952 and was followed in 1954 by his orchestral Poem-Rhapsody. The Sonata for Violin and Piano was produced in 1959, followed by the Cello Concerto, which was written for and dedicated to Mstislav Rostropovich. Among his last compositions were the Six Pictures for Piano (1965), the Third String Quartet (1979) and the Nocturne for piano and symphonic jazz ensemble (1981).  Eduard Ivanovich Bagdasarian was one of the most significant and respected key figure in the modern development of Armenian music. While he steadily built up a reputation as a composer of concert music, from the mid-1950s he became increasingly involved in film music and incidental music for the stage, and later for television as well, allowing himself to be drawn into more popular contemporary genres without compromising the standards of his musical upbringing. In the 1960s he was head of instrumental and pop music for Armenian radio, and many of his songs became widely popular. His national prominence gave him a real standing as an ambassador for Armenian music, which he fulfilled many times as a delegate to the other Soviet republics, and abroad as far as Poland and Lebanon. He was also a frequent juror in many USSR competitions for both piano-playing and composition.

Eduard Ivanovich Bagdasarian was one of the most significant and respected key figure in the modern development of Armenian music. While he steadily built up a reputation as a composer of concert music, from the mid-1950s he became increasingly involved in film music and incidental music for the stage, and later for television as well, allowing himself to be drawn into more popular contemporary genres without compromising the standards of his musical upbringing. In the 1960s he was head of instrumental and pop music for Armenian radio, and many of his songs became widely popular. His national prominence gave him a real standing as an ambassador for Armenian music, which he fulfilled many times as a delegate to the other Soviet republics, and abroad as far as Poland and Lebanon. He was also a frequent juror in many USSR competitions for both piano-playing and composition.  A brilliant pianist, improviser, noted conductor and selfless champion of other composers, Balakirev is surprisingly little known today. Yet as leader of the Russian composers known as ‘The Mighty Handful’, Rimsky-Korsakov, Mussorgsky, Borodin and Cui, he strongly influenced not only their work but also that of Tchaikovsky, Debussy, Ravel and Stravinsky, setting the standard by which others were judged. In addition to a large output of piano music and songs, Balakirev wrote two symphonies, several symphonic poems, works for piano and orchestra, choral music and incidental music for Shakespeare’s King Lear.

A brilliant pianist, improviser, noted conductor and selfless champion of other composers, Balakirev is surprisingly little known today. Yet as leader of the Russian composers known as ‘The Mighty Handful’, Rimsky-Korsakov, Mussorgsky, Borodin and Cui, he strongly influenced not only their work but also that of Tchaikovsky, Debussy, Ravel and Stravinsky, setting the standard by which others were judged. In addition to a large output of piano music and songs, Balakirev wrote two symphonies, several symphonic poems, works for piano and orchestra, choral music and incidental music for Shakespeare’s King Lear.  Georges Baz attended a francophone Jesuit school, and he had the French organist Bertrand Robillard to thank for his solid musical foundation. Baz did not study in France, however, but in Siena, having been given a grant by the Italian Institute of Culture. Even then he was earning his living working in a bank, and throughout his professional life he pursued a dual career, rising to be head of the central bank of Lebanon, whilst teaching at the Conservatory in Beirut and writing reviews for the newspaper L’Orient. He was also co-founder of the Baalbek International Festival.

Georges Baz attended a francophone Jesuit school, and he had the French organist Bertrand Robillard to thank for his solid musical foundation. Baz did not study in France, however, but in Siena, having been given a grant by the Italian Institute of Culture. Even then he was earning his living working in a bank, and throughout his professional life he pursued a dual career, rising to be head of the central bank of Lebanon, whilst teaching at the Conservatory in Beirut and writing reviews for the newspaper L’Orient. He was also co-founder of the Baalbek International Festival.  Beethoven did much to enlarge the possibilities of music and widen the horizons of later generations of composers.

Beethoven did much to enlarge the possibilities of music and widen the horizons of later generations of composers.  A decisive factor in Lars Aksel Bisgaard’s choice of career was that in the winter of 1965–66 when, as a schoolboy, he participated in Finn Lykkebo’s knowledgeable and inspiring lessons in musical appreciation at evening classes. After passing his school-leaving exams, Bisgaard acquired the necessary knowledge first by studying musicology at the University of Copenhagen (1966–69) and then by following in Lykkebo’s footsteps as a student at the Royal Danish Academy of Music with music theory and music history as his main subjects (1969–75). Immediately after that, he commenced studies of composition under Per Nørgård at the Academy of Music in Aarhus (1975–81).

A decisive factor in Lars Aksel Bisgaard’s choice of career was that in the winter of 1965–66 when, as a schoolboy, he participated in Finn Lykkebo’s knowledgeable and inspiring lessons in musical appreciation at evening classes. After passing his school-leaving exams, Bisgaard acquired the necessary knowledge first by studying musicology at the University of Copenhagen (1966–69) and then by following in Lykkebo’s footsteps as a student at the Royal Danish Academy of Music with music theory and music history as his main subjects (1969–75). Immediately after that, he commenced studies of composition under Per Nørgård at the Academy of Music in Aarhus (1975–81).  Described by Saint-Saëns as ‘the most remarkable of the young British composers’, York Bowen was widely known as a pianist and as a composer, his fame reaching its zenith in the years immediately preceding the First World War. The youngest of three sons, he was born on 22 February 1884 at Crouch Hill, London. In 1898 he won a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Music, studying piano with Tobias Matthay and composition with Frederick Corder until 1905. A gifted student, he won many prizes for piano and composition, including the Worshipful Company of Musicians’ Medal. With regular performances at the Queen’s Hall and later at the Royal Albert Hall, his piano playing received critical acclaim for its technical and artistic excellence. In addition to his successful career as a solo (virtuoso) pianist, he formed celebrated duos with the great viola player Lionel Tertis and the pianist Harry Isaacs. Active as a musician to the last, Bowen died suddenly at his home in Hampstead at the age of 77 on 23 November 1961.

Described by Saint-Saëns as ‘the most remarkable of the young British composers’, York Bowen was widely known as a pianist and as a composer, his fame reaching its zenith in the years immediately preceding the First World War. The youngest of three sons, he was born on 22 February 1884 at Crouch Hill, London. In 1898 he won a scholarship to the Royal Academy of Music, studying piano with Tobias Matthay and composition with Frederick Corder until 1905. A gifted student, he won many prizes for piano and composition, including the Worshipful Company of Musicians’ Medal. With regular performances at the Queen’s Hall and later at the Royal Albert Hall, his piano playing received critical acclaim for its technical and artistic excellence. In addition to his successful career as a solo (virtuoso) pianist, he formed celebrated duos with the great viola player Lionel Tertis and the pianist Harry Isaacs. Active as a musician to the last, Bowen died suddenly at his home in Hampstead at the age of 77 on 23 November 1961.  The son of an Italian musician father and a German pianist mother, Ferruccio Busoni represented a remarkable synthesis of two differing attitudes to music, while winning an outstanding reputation as a piano virtuoso.

The son of an Italian musician father and a German pianist mother, Ferruccio Busoni represented a remarkable synthesis of two differing attitudes to music, while winning an outstanding reputation as a piano virtuoso.  Teresa Carreño’s immense musical talent became apparent at an early age. She performed for both Gioachino Rossini and Franz Liszt; she met with eminent musicians such as Charles Gounod and Camille Saint-Saëns, and Anton Rubinstein himself insisted on giving her lessons, and even later on he was to hold her in high regard. Her repertoire by this point included works by Beethoven and Chopin; apart from that she mainly performed opera paraphrases, as was customary for a pianist of her time. She also presented her own compositions in many concerts, which appear very sophisticated considering her young age.

Teresa Carreño’s immense musical talent became apparent at an early age. She performed for both Gioachino Rossini and Franz Liszt; she met with eminent musicians such as Charles Gounod and Camille Saint-Saëns, and Anton Rubinstein himself insisted on giving her lessons, and even later on he was to hold her in high regard. Her repertoire by this point included works by Beethoven and Chopin; apart from that she mainly performed opera paraphrases, as was customary for a pianist of her time. She also presented her own compositions in many concerts, which appear very sophisticated considering her young age.  Johann Baptist Cramer established a formidable reputation as a pianist. He made his first appearance as an infant prodigy at the age of 10 and three years later, in 1784, joined Muzio Clementi, briefly his teacher, in a sonata for two pianos. In 1788 Cramer embarked on his first European tour, which took him to Paris and to Berlin, while in London he made his name as one of the leading pianists of the day and as a successful teacher. As a composer he had been prolific, and he had also been involved in music publishing and in the sale of pianos, his name continuing its commercial connection in London well into the twentieth century.

Johann Baptist Cramer established a formidable reputation as a pianist. He made his first appearance as an infant prodigy at the age of 10 and three years later, in 1784, joined Muzio Clementi, briefly his teacher, in a sonata for two pianos. In 1788 Cramer embarked on his first European tour, which took him to Paris and to Berlin, while in London he made his name as one of the leading pianists of the day and as a successful teacher. As a composer he had been prolific, and he had also been involved in music publishing and in the sale of pianos, his name continuing its commercial connection in London well into the twentieth century.  Dr Tanya Ekanayaka is an internationally acclaimed and award-winning Sri Lankan-British concert composer-pianist. Although trained as a pianist, her compositional skills are the result of a purely intuitive and natural development. Influenced by her multifaceted background, multilingualism, ambidexterity and partial colour synaesthesia her works which she describes as ‘deeply autobiographical’ and which evolve when she is at the piano (and at times in her dreams), have not been scored in any form but remain precisely frozen in her memory once evolved. Consistent with her interdisciplinary background, she holds a doctorate for interdisciplinary research involving Linguistics and Musicology from The University of Edinburgh, where she has also been engaged part time in academic teaching since 2007, as well as advanced academic and professional qualifications in Music Performance, Linguistics and Literature.

Dr Tanya Ekanayaka is an internationally acclaimed and award-winning Sri Lankan-British concert composer-pianist. Although trained as a pianist, her compositional skills are the result of a purely intuitive and natural development. Influenced by her multifaceted background, multilingualism, ambidexterity and partial colour synaesthesia her works which she describes as ‘deeply autobiographical’ and which evolve when she is at the piano (and at times in her dreams), have not been scored in any form but remain precisely frozen in her memory once evolved. Consistent with her interdisciplinary background, she holds a doctorate for interdisciplinary research involving Linguistics and Musicology from The University of Edinburgh, where she has also been engaged part time in academic teaching since 2007, as well as advanced academic and professional qualifications in Music Performance, Linguistics and Literature.  In the vast Eastern European diaspora of 20th Century music, few composers can claim the audacity and originality of George Enescu. Enescu was barely in his teens when he commanded the attention of Europe’s musical aristocracy as a virtuoso violinist. In 1895 he entered the Paris Conservatory, where he cultivated his compositional gifts as a student of Fauré and Massenet, astounding all who knew him with his consummate virtuosity at the piano, cello, and organ as well. For nearly a half century the name Enescu was on the lips of every major concert artist. Among them were his classmate at the Conservatoire, Alfred Cortot, his godson Dinu Lipatti; Gustav Mahler, his student Yehudi Menuhin, David Oistrakh, and Clara Haskil, to name only a few.

In the vast Eastern European diaspora of 20th Century music, few composers can claim the audacity and originality of George Enescu. Enescu was barely in his teens when he commanded the attention of Europe’s musical aristocracy as a virtuoso violinist. In 1895 he entered the Paris Conservatory, where he cultivated his compositional gifts as a student of Fauré and Massenet, astounding all who knew him with his consummate virtuosity at the piano, cello, and organ as well. For nearly a half century the name Enescu was on the lips of every major concert artist. Among them were his classmate at the Conservatoire, Alfred Cortot, his godson Dinu Lipatti; Gustav Mahler, his student Yehudi Menuhin, David Oistrakh, and Clara Haskil, to name only a few.  Helge Evju was taught piano mainly by his aunt, the concert pianist Aslaug Evju Blackstad. He worked as a pianist-répetiteur for the Norwegian Opera (now the Norwegian Opera and Ballet), where he stayed until retirement in 2011. His assignments for the Opera grew with the years to comprise concerts (touring the entire country), soloistic appearances with the orchestra, regular performances in the Sunday chamber concerts, lectures, texts, translations, arrangements, orchestrations and compositions. To this day he still makes guest appearances, and will conduct a comic operatic show from the piano in the spring of 2015. He has written songs, piano pieces and several operatic arias and scenes.

Helge Evju was taught piano mainly by his aunt, the concert pianist Aslaug Evju Blackstad. He worked as a pianist-répetiteur for the Norwegian Opera (now the Norwegian Opera and Ballet), where he stayed until retirement in 2011. His assignments for the Opera grew with the years to comprise concerts (touring the entire country), soloistic appearances with the orchestra, regular performances in the Sunday chamber concerts, lectures, texts, translations, arrangements, orchestrations and compositions. To this day he still makes guest appearances, and will conduct a comic operatic show from the piano in the spring of 2015. He has written songs, piano pieces and several operatic arias and scenes.  Friedman’s compositions are largely miniatures even if grouped into sets. He is the master of the character piece. Writing in late German Romantic style, his compositions are often harmonically complex although tonal. Friedman does not employ the sensuality of a Scriabin or a Szymanowski but allows the beauty and poignancy of the melody to shine. Rhythms are traditional and within the genre depicted. Pianistically accessible, Friedman’s works demand technical and musical perfection.

Friedman’s compositions are largely miniatures even if grouped into sets. He is the master of the character piece. Writing in late German Romantic style, his compositions are often harmonically complex although tonal. Friedman does not employ the sensuality of a Scriabin or a Szymanowski but allows the beauty and poignancy of the melody to shine. Rhythms are traditional and within the genre depicted. Pianistically accessible, Friedman’s works demand technical and musical perfection.  Gerhard Frommel was born on 7 August 1906 in Karlsruhe. He studied first with Hermann Grabner and then, from 1926 to 1928, attended masterclasses given by Hans Pfitzner. He was Professor of Composition at the universities of Frankfurt-am-Main and Stuttgart, among other institutions, and during the war he was active in the Frankfurt Musikhochschule. After 1950, tonal music, including that of Frommel, was regarded in Germany as fascist and was supplanted by dodecaphony and its further developments. Frommel died on 22 June 1984 in Stuttgart.

Gerhard Frommel was born on 7 August 1906 in Karlsruhe. He studied first with Hermann Grabner and then, from 1926 to 1928, attended masterclasses given by Hans Pfitzner. He was Professor of Composition at the universities of Frankfurt-am-Main and Stuttgart, among other institutions, and during the war he was active in the Frankfurt Musikhochschule. After 1950, tonal music, including that of Frommel, was regarded in Germany as fascist and was supplanted by dodecaphony and its further developments. Frommel died on 22 June 1984 in Stuttgart.  Anis Fuleihan made an intensive study of Middle Eastern traditional music as early as the 1920s. Inasmuch as he was director of the Beirut Conservatory from 1953 to 1960, and conductor of Beirut’s orchestra during the same period, Fuleihan is one of the founding fathers of Lebanese symphonic music. His orchestral works were premièred by the likes of John Barbirolli and Leopold Stokowski, and he himself frequently conducted the New York Philharmonic. After teaching at Indiana University for many years, Fuleihan held appointments first in Beirut and later in Tunisia, where he founded the Orchestre Classique de Tunis in 1962. Not only his biography, but also his music gives the impression that he was a focussed and vigorous cosmopolitan.

Anis Fuleihan made an intensive study of Middle Eastern traditional music as early as the 1920s. Inasmuch as he was director of the Beirut Conservatory from 1953 to 1960, and conductor of Beirut’s orchestra during the same period, Fuleihan is one of the founding fathers of Lebanese symphonic music. His orchestral works were premièred by the likes of John Barbirolli and Leopold Stokowski, and he himself frequently conducted the New York Philharmonic. After teaching at Indiana University for many years, Fuleihan held appointments first in Beirut and later in Tunisia, where he founded the Orchestre Classique de Tunis in 1962. Not only his biography, but also his music gives the impression that he was a focussed and vigorous cosmopolitan.  Boghos Gelalian earned his living as a pianist in nightclubs, then working as a music arranger for radio. As musical advisor to the Rahbani brothers, he went on to play a significant role in the singer Fairuz’s rise to become a legendary icon of Arabic music. Fairuz’s son Ziad Rahbani, who later became the Lebanese left wing’s figurehead, was also one of his pupils. Despite his familiarity with jazz and light music and the Turkish and Arabic traditions, Gelalian’s own compositions are uncompromisingly modern. Their intense chromaticism occasionally verges on atonality, whilst also—astonishingly—being derived from Armenian and oriental modes.

Boghos Gelalian earned his living as a pianist in nightclubs, then working as a music arranger for radio. As musical advisor to the Rahbani brothers, he went on to play a significant role in the singer Fairuz’s rise to become a legendary icon of Arabic music. Fairuz’s son Ziad Rahbani, who later became the Lebanese left wing’s figurehead, was also one of his pupils. Despite his familiarity with jazz and light music and the Turkish and Arabic traditions, Gelalian’s own compositions are uncompromisingly modern. Their intense chromaticism occasionally verges on atonality, whilst also—astonishingly—being derived from Armenian and oriental modes.  In a period in which American nationalist music was developing with composers of the calibre of Aaron Copland and others trained in Europe, George Gershwin, the son of Russian Jewish immigrant parents, went some way towards bridging the wide gap between Tin Pan Alley and serious music. He won success as a composer of light music, songs and musicals, but in a relatively small number of compositions he made forays into a new form of classical repertoire.

In a period in which American nationalist music was developing with composers of the calibre of Aaron Copland and others trained in Europe, George Gershwin, the son of Russian Jewish immigrant parents, went some way towards bridging the wide gap between Tin Pan Alley and serious music. He won success as a composer of light music, songs and musicals, but in a relatively small number of compositions he made forays into a new form of classical repertoire.  Piano is Philip Glass’ primary instrument (he also studied violin and flute); he composes at the keyboard. With its seemingly contradictory elements of lyricism and percussiveness, it is in some ways the ideal medium for Glass’ musical language. With its deep roots in tradition (spanning the Classical, Romantic and Modern eras), the instrument embodies the composer’s desire to merge new ideas with classic forms. It is perhaps via piano (and, by extension, keyboard) that performers and listeners can make the most direct and personal contact with Glass’ musical genius.

Piano is Philip Glass’ primary instrument (he also studied violin and flute); he composes at the keyboard. With its seemingly contradictory elements of lyricism and percussiveness, it is in some ways the ideal medium for Glass’ musical language. With its deep roots in tradition (spanning the Classical, Romantic and Modern eras), the instrument embodies the composer’s desire to merge new ideas with classic forms. It is perhaps via piano (and, by extension, keyboard) that performers and listeners can make the most direct and personal contact with Glass’ musical genius.  Glinka is commonly regarded as the founder of Russian nationalism in music. His influence on Balakirev, self-appointed leader of the later group of five nationalist composers, was considerable. As a child he had some lessons from the Irish pianist John Field, but his association with music remained purely amateur until visits to Italy and in 1833 to Berlin allowed concentrated study and subsequently a greater degree of assurance in his composition, which won serious attention both at home and abroad. His Russian operas offered a synthesis of Western operatic form with Russian melody, while his orchestral music, with skillful instrumentation, offered a combination of the traditional and the exotic. Glinka died in Berlin in 1857.

Glinka is commonly regarded as the founder of Russian nationalism in music. His influence on Balakirev, self-appointed leader of the later group of five nationalist composers, was considerable. As a child he had some lessons from the Irish pianist John Field, but his association with music remained purely amateur until visits to Italy and in 1833 to Berlin allowed concentrated study and subsequently a greater degree of assurance in his composition, which won serious attention both at home and abroad. His Russian operas offered a synthesis of Western operatic form with Russian melody, while his orchestral music, with skillful instrumentation, offered a combination of the traditional and the exotic. Glinka died in Berlin in 1857.  Godard was a prolific composer and within the course of his short life he wrote three symphonies, four concertos, eight operas, three string quartets, four violin sonatas, and a tremendous range of further chamber works, piano solos and songs.

Godard was a prolific composer and within the course of his short life he wrote three symphonies, four concertos, eight operas, three string quartets, four violin sonatas, and a tremendous range of further chamber works, piano solos and songs.  Gouvy began piano lessons with a private tutor at the age of eight, and was educated in France—Sarreguemines, then Metz—developing a keen interest in Classical Greek culture and in modern languages—not only German, which he spoke fluently, but English and Italian as well. In 1837 he went to Paris to study law, continuing his piano lessons with a pupil of the pianist and composer Henri Herz (1803–1888). Two years later, he made up his mind to abandon any thoughts of a career in the law and to devote himself to music. He stood out in French musical life as a composer of orchestral and chamber music.

Gouvy began piano lessons with a private tutor at the age of eight, and was educated in France—Sarreguemines, then Metz—developing a keen interest in Classical Greek culture and in modern languages—not only German, which he spoke fluently, but English and Italian as well. In 1837 he went to Paris to study law, continuing his piano lessons with a pupil of the pianist and composer Henri Herz (1803–1888). Two years later, he made up his mind to abandon any thoughts of a career in the law and to devote himself to music. He stood out in French musical life as a composer of orchestral and chamber music.  The essence of Grainger’s music is perhaps most evident in his output for piano. This was an instrument his mastery of which had led to his early recognition as a virtuoso performer.

The essence of Grainger’s music is perhaps most evident in his output for piano. This was an instrument his mastery of which had led to his early recognition as a virtuoso performer.  Edvard Grieg is the most important Norwegian composer of the later 19th century, a period of growing national consciousness. As a child, he was encouraged by the violinist Ole Bull, a friend of his parents, and studied at the Leipzig Conservatory on his suggestion. After a period at home in Norway he moved to Copenhagen, where he met the young composer Rikard Nordraak, an enthusiastic champion of Norwegian music and a decisive influence on him. Grieg’s own performances of Norwegian music, often with his wife, the singer Nina Hagerup, established him as a leading figure in the music of his own country, bringing subsequent collaboration in the theatre with Bjørnson and with Ibsen. He continued to divide his time between composition and activity in the concert hall until his death in 1907.

Edvard Grieg is the most important Norwegian composer of the later 19th century, a period of growing national consciousness. As a child, he was encouraged by the violinist Ole Bull, a friend of his parents, and studied at the Leipzig Conservatory on his suggestion. After a period at home in Norway he moved to Copenhagen, where he met the young composer Rikard Nordraak, an enthusiastic champion of Norwegian music and a decisive influence on him. Grieg’s own performances of Norwegian music, often with his wife, the singer Nina Hagerup, established him as a leading figure in the music of his own country, bringing subsequent collaboration in the theatre with Bjørnson and with Ibsen. He continued to divide his time between composition and activity in the concert hall until his death in 1907.  As a composer, Philip Hammond has been regularly commissioned by individuals and groups in Ireland and in Britain such as the Ulster Orchestra, the contemporary ensemble Lontano, the Brodsky String Quartet, James Galway, Sarah Walker, Suzanne Murphy, Tasmin Little, Barry Douglas, Nikolai Demidenko and Ann Murray. He is often commissioned as an “occasional” composer and his Waterfront Fanfares (1997) were written to open the Waterfront Hall in Belfast. His …the starry dynamo in the machinery of night… was specially commissioned by Queen’s University to celebrate the visit of President Clinton in May 2001. The National Youth Orchestra of Ireland commissioned and performed his Carnavalesque for Double Orchestra and Percussion in July 2003. In 2005, his …while the sun shines was commissioned by BBC Radio Three to celebrate the music of the great Irish conductor and composer Sir Hamilton Harty (in 1979, Philip Hammond contributed two biographical chapters to a book on Sir Hamilton Harty (Blackstaff, 1979). Philip Hammond’s Requiem for the Lost Souls of the Titanic for choruses and brass was premiered in April 2012 on the exact hundredth anniversary of the ship’s demise.

As a composer, Philip Hammond has been regularly commissioned by individuals and groups in Ireland and in Britain such as the Ulster Orchestra, the contemporary ensemble Lontano, the Brodsky String Quartet, James Galway, Sarah Walker, Suzanne Murphy, Tasmin Little, Barry Douglas, Nikolai Demidenko and Ann Murray. He is often commissioned as an “occasional” composer and his Waterfront Fanfares (1997) were written to open the Waterfront Hall in Belfast. His …the starry dynamo in the machinery of night… was specially commissioned by Queen’s University to celebrate the visit of President Clinton in May 2001. The National Youth Orchestra of Ireland commissioned and performed his Carnavalesque for Double Orchestra and Percussion in July 2003. In 2005, his …while the sun shines was commissioned by BBC Radio Three to celebrate the music of the great Irish conductor and composer Sir Hamilton Harty (in 1979, Philip Hammond contributed two biographical chapters to a book on Sir Hamilton Harty (Blackstaff, 1979). Philip Hammond’s Requiem for the Lost Souls of the Titanic for choruses and brass was premiered in April 2012 on the exact hundredth anniversary of the ship’s demise.  Adolf von Henselt was born in the Bavarian town of Schwabach on 9 May 1814. Praised by Liszt for his unequalled cantabile playing, Henselt belonged to a galaxy of star pianists who were all of a similar age. These included Chopin, Schumann, Thalberg and, of course, Liszt. Although Henselt began his musical studies on the violin, he soon changed to the piano and made spectacularly rapid progress. It was as a child that he developed a strong and permanent affinity with the musical Romanticism of Carl Maria von Weber.

Adolf von Henselt was born in the Bavarian town of Schwabach on 9 May 1814. Praised by Liszt for his unequalled cantabile playing, Henselt belonged to a galaxy of star pianists who were all of a similar age. These included Chopin, Schumann, Thalberg and, of course, Liszt. Although Henselt began his musical studies on the violin, he soon changed to the piano and made spectacularly rapid progress. It was as a child that he developed a strong and permanent affinity with the musical Romanticism of Carl Maria von Weber.  Franz Anton was born into a respected family of middle-class town-dwellers. His ancestors included mayors of Rottenburg. He was sent to Vienna to study law when he was still only 14, but music in general, and playing the organ in particular, increasingly took over. It was in the Imperial capital that he achieved his first successes with highly imaginative compositions. Founding his first publishing house was a pioneering move, but not one blessed with any lasting commercial success. It wasn’t until he and Ambrosius Kühnel set up the “Bureau de musique”—now C.F. Peters—in Leipzig in 1800 that he succeeded in establishing a publisher with a global reach. However, Hoffmeister seems to have seen himself first and foremost as a composer and organist, for having established the Bureau, he made the firm over to its employees as early as 1805 (not without a measure of conflict) and returned to his adopted home, Vienna, where he was well respected until his death in 1812.

Franz Anton was born into a respected family of middle-class town-dwellers. His ancestors included mayors of Rottenburg. He was sent to Vienna to study law when he was still only 14, but music in general, and playing the organ in particular, increasingly took over. It was in the Imperial capital that he achieved his first successes with highly imaginative compositions. Founding his first publishing house was a pioneering move, but not one blessed with any lasting commercial success. It wasn’t until he and Ambrosius Kühnel set up the “Bureau de musique”—now C.F. Peters—in Leipzig in 1800 that he succeeded in establishing a publisher with a global reach. However, Hoffmeister seems to have seen himself first and foremost as a composer and organist, for having established the Bureau, he made the firm over to its employees as early as 1805 (not without a measure of conflict) and returned to his adopted home, Vienna, where he was well respected until his death in 1812.  Like so many other performing artists of the past, Hofmann was equally at home composing. His output includes a symphony, five piano concertos and a considerable quantity of solo piano music. Some of his smaller pieces appeared under the pseudonym Dvorsky (which is actually the Polish equivalent of Hofmann). He delighted in the fiction that Michel Dvorsky was a reclusive young Frenchman who modestly sent his efforts to Hofmann for evaluation. The humour behind this innocent little deceit is akin to that of the violinist Fritz Kreisler, who famously ascribed the names of little-known composers to some of his own slighter pieces. Hofmann’s compositions are positioned very firmly in the Romantic tradition. To his contemporaries, familiar with the recent work of Debussy or Scriabin, they probably came across as old-fashioned, but now that sufficient time has passed we can simply enjoy the music on its own terms without worrying about whether it is ‘modern’ enough.

Like so many other performing artists of the past, Hofmann was equally at home composing. His output includes a symphony, five piano concertos and a considerable quantity of solo piano music. Some of his smaller pieces appeared under the pseudonym Dvorsky (which is actually the Polish equivalent of Hofmann). He delighted in the fiction that Michel Dvorsky was a reclusive young Frenchman who modestly sent his efforts to Hofmann for evaluation. The humour behind this innocent little deceit is akin to that of the violinist Fritz Kreisler, who famously ascribed the names of little-known composers to some of his own slighter pieces. Hofmann’s compositions are positioned very firmly in the Romantic tradition. To his contemporaries, familiar with the recent work of Debussy or Scriabin, they probably came across as old-fashioned, but now that sufficient time has passed we can simply enjoy the music on its own terms without worrying about whether it is ‘modern’ enough.  Afshin Jaberi was born in 1973 into an Iranian family residing in Qatar. Unable to receive formal musical instruction there, he began to develop his interest in the subject by himself. His musical education began properly in 1991 in Hungary, where he attended the Franz Liszt Academy of Music and received his bachelor’s degree in music education. His rapid progress attracted the attention of his teachers and, after two and a half years as a part-time student, he was readily accepted into the academy for full-time study. Besides the distinct progress he made in piano performance, his compositions also attracted attention, especially his First Ballade, written at the age of eighteen; another eight were to follow. His compositions are influenced by the spirit of his faith, from which the acts of heroism and sacrifice of the central figures are reflected in his Ballades. This background has enabled him to bring together the sounds of East and West in his compositions.

Afshin Jaberi was born in 1973 into an Iranian family residing in Qatar. Unable to receive formal musical instruction there, he began to develop his interest in the subject by himself. His musical education began properly in 1991 in Hungary, where he attended the Franz Liszt Academy of Music and received his bachelor’s degree in music education. His rapid progress attracted the attention of his teachers and, after two and a half years as a part-time student, he was readily accepted into the academy for full-time study. Besides the distinct progress he made in piano performance, his compositions also attracted attention, especially his First Ballade, written at the age of eighteen; another eight were to follow. His compositions are influenced by the spirit of his faith, from which the acts of heroism and sacrifice of the central figures are reflected in his Ballades. This background has enabled him to bring together the sounds of East and West in his compositions.  Like her composer father, Kaprálová was drawn to piano as her natural instrument, and piano compositions are well represented in her relatively large creative output that includes about fifty compositions. Piano also played a crucial role in her music as a compositional tool with which she experimented in both smaller and larger forms. It is therefore not surprising that her most original and sophisticated works are for this instrument: from her Sonata appassionata and Piano Concerto in D Minor to April Preludes and Variations sur le carillon de l’église St.-Etienne-du-Mont (and the Martinu–influenced, neoclassical Partita in which piano also plays an important percussive role). Piano compositions arguably represent the best of Kaprálová’s music which abounds in fresh and bold ideas, humour, passion and tenderness, and is imbued with youthful energy.

Like her composer father, Kaprálová was drawn to piano as her natural instrument, and piano compositions are well represented in her relatively large creative output that includes about fifty compositions. Piano also played a crucial role in her music as a compositional tool with which she experimented in both smaller and larger forms. It is therefore not surprising that her most original and sophisticated works are for this instrument: from her Sonata appassionata and Piano Concerto in D Minor to April Preludes and Variations sur le carillon de l’église St.-Etienne-du-Mont (and the Martinu–influenced, neoclassical Partita in which piano also plays an important percussive role). Piano compositions arguably represent the best of Kaprálová’s music which abounds in fresh and bold ideas, humour, passion and tenderness, and is imbued with youthful energy.  Kazhlaev’s catalogue ranges from nationalist orchestral works to circus numbers, ballet to operetta, musical to revue commissions to songs and romances—all overtly harmonic, tuneful and vibrantly imagined. His jazz, big band, light music and film output, getting on for two hundred scores, affirms the studio professional working against the clock.

Kazhlaev’s catalogue ranges from nationalist orchestral works to circus numbers, ballet to operetta, musical to revue commissions to songs and romances—all overtly harmonic, tuneful and vibrantly imagined. His jazz, big band, light music and film output, getting on for two hundred scores, affirms the studio professional working against the clock.  Although Khachaturian was a relatively late starter as a composer, the majority of his works date from the earlier half of his career. These include three symphonies (1934, 1943 and 1947), concertos for piano, violin and cello (1936, 1940 and 1946), and the ballets Gayaneh (1942) and Spartacus (1954). Thereafter his conducting and administration duties left much less time for composition, though mention ought to be made of the Concerto-Rhapsodies for violin, for cello and for piano (1961, 1963 and 1968), as well as unaccompanied sonatas for cello, violin and viola (1974–6) that marked a belated return to chamber music. He also left a number of piano works, along with numerous scores for theatre and cinema—the suites of which, along with those from his ballets, kept his name alive in the concert hall despite the absence of larger symphonic works. Not in doubt is the expressive immediacy of his music, with its sensuous yet direct melodic writing, highly resourceful orchestration and elemental rhythmic drive—resulting in a popularity equalled by very few composers of his generation.

Although Khachaturian was a relatively late starter as a composer, the majority of his works date from the earlier half of his career. These include three symphonies (1934, 1943 and 1947), concertos for piano, violin and cello (1936, 1940 and 1946), and the ballets Gayaneh (1942) and Spartacus (1954). Thereafter his conducting and administration duties left much less time for composition, though mention ought to be made of the Concerto-Rhapsodies for violin, for cello and for piano (1961, 1963 and 1968), as well as unaccompanied sonatas for cello, violin and viola (1974–6) that marked a belated return to chamber music. He also left a number of piano works, along with numerous scores for theatre and cinema—the suites of which, along with those from his ballets, kept his name alive in the concert hall despite the absence of larger symphonic works. Not in doubt is the expressive immediacy of his music, with its sensuous yet direct melodic writing, highly resourceful orchestration and elemental rhythmic drive—resulting in a popularity equalled by very few composers of his generation.  Born in Tripoli in 1967 and with a doctorate in musicology, Houtaf Khoury represents the younger generation of Lebanese composers. The formative influences on his work came from the Ukraine, from Kiev, where a grant enabled him to pursue his studies from 1988 to 1997. Khoury shares the scepticism of composers such as Shostakovich, Schnittke and Kancheli vis-à-vis the avant-garde’s obsession with material and the belief that music always conveys a message. His orchestral works, chamber music and compositions for piano are pleas for a more humane world.

Born in Tripoli in 1967 and with a doctorate in musicology, Houtaf Khoury represents the younger generation of Lebanese composers. The formative influences on his work came from the Ukraine, from Kiev, where a grant enabled him to pursue his studies from 1988 to 1997. Khoury shares the scepticism of composers such as Shostakovich, Schnittke and Kancheli vis-à-vis the avant-garde’s obsession with material and the belief that music always conveys a message. His orchestral works, chamber music and compositions for piano are pleas for a more humane world.  Komitas was one of the first Armenian musicians to undergo classical Western musical training, in Berlin, in addition to music education in his own country. He was educated in a theological seminary in Vagharshapat, and ordained a priest in 1894. A gifted singer, he studied liturgical singing and early Armenian chant notation. He also developed a keen interest in folksong, and collected melodies which he would then harmonise for choral performance. He published both folksong collections and writings on Armenian church melodies, and his work laid the foundations for the development of a clearly defined national musical style. He moved to Constantinople in 1910, a city with a significant Armenian population, and continued to compose (predominantly vocal music), conduct and research.

Komitas was one of the first Armenian musicians to undergo classical Western musical training, in Berlin, in addition to music education in his own country. He was educated in a theological seminary in Vagharshapat, and ordained a priest in 1894. A gifted singer, he studied liturgical singing and early Armenian chant notation. He also developed a keen interest in folksong, and collected melodies which he would then harmonise for choral performance. He published both folksong collections and writings on Armenian church melodies, and his work laid the foundations for the development of a clearly defined national musical style. He moved to Constantinople in 1910, a city with a significant Armenian population, and continued to compose (predominantly vocal music), conduct and research.  Leopold Koželuch was an esteemed contemporary of Mozart, and in many circles considered the finer composer. He was an early champion of the fortepiano and his Keyboard Sonatas are a treasure trove of late eighteenth-century Viennese keyboard style, including perfect examples of the form and foreshadowing Beethoven and Schubert.

Leopold Koželuch was an esteemed contemporary of Mozart, and in many circles considered the finer composer. He was an early champion of the fortepiano and his Keyboard Sonatas are a treasure trove of late eighteenth-century Viennese keyboard style, including perfect examples of the form and foreshadowing Beethoven and Schubert.  Johan Kvandal was born in 1919. His parents were the artist Lissa (Amunda) and the composer David Monrad Johansen, and this early exposure to the arts proved extremely influential. He studied composition with Geirr Tveitt from 1937–1942 and with Joseph Marx in Vienna from 1942–1944. After the war, he completed his studies at the Norwegian Academy of Music, majoring first in conducting in 1947 and then in organ in 1951.

In the early years Kvandal was, like many other composers of his generation, influenced by the predominantly nationalist trends of the 1920s and 1930s. He sought in this period to combine elements from Norwegian folk music with classical forms.

Johan Kvandal was born in 1919. His parents were the artist Lissa (Amunda) and the composer David Monrad Johansen, and this early exposure to the arts proved extremely influential. He studied composition with Geirr Tveitt from 1937–1942 and with Joseph Marx in Vienna from 1942–1944. After the war, he completed his studies at the Norwegian Academy of Music, majoring first in conducting in 1947 and then in organ in 1951.

In the early years Kvandal was, like many other composers of his generation, influenced by the predominantly nationalist trends of the 1920s and 1930s. He sought in this period to combine elements from Norwegian folk music with classical forms.  Like his older colleagues Guy Ropartz and Louis Aubert, he was of Breton origin, and once recalled: “The first music I heard was the folk songs of Brittany, which were very beautiful—they seduced me, lit the flame of love within me…” That Breton soundworld of his childhood was soon broadened and enriched when he began to teach himself harmony and music theory. He went to his first concerts and opera performances in Brest, and started composing before he sat his baccalauréat exams in 1899. Like Albert Roussel a few years earlier, Le Flem heard the call of the sea and planned to study at the École Navale, but in the event, his poor eyesight meant a maritime career was out of the question. Instead he went to Paris, studying with Lavignac at the Conservatoire—where the academic teaching style failed to enthuse him—as well as graduating in philosophy from the Sorbonne.

Like his older colleagues Guy Ropartz and Louis Aubert, he was of Breton origin, and once recalled: “The first music I heard was the folk songs of Brittany, which were very beautiful—they seduced me, lit the flame of love within me…” That Breton soundworld of his childhood was soon broadened and enriched when he began to teach himself harmony and music theory. He went to his first concerts and opera performances in Brest, and started composing before he sat his baccalauréat exams in 1899. Like Albert Roussel a few years earlier, Le Flem heard the call of the sea and planned to study at the École Navale, but in the event, his poor eyesight meant a maritime career was out of the question. Instead he went to Paris, studying with Lavignac at the Conservatoire—where the academic teaching style failed to enthuse him—as well as graduating in philosophy from the Sorbonne.  Although Lourié studied at the St Petersburg Conservatoire, where his composition teachers included Alexander Glazunov, his main musical influence in his youth was Alexander Scriabin, whose late piano works fascinated him. He was also greatly inspired by the Futurists, and he made musical settings of verses by poets such as Anna Akhmatova (with whom he conducted a passionate affair). Vladimir Mayakovsky and Alexander Blok affected him profoundly through the eloquence of their writing and the allure of their political views, which appealed to Lourié’s own radical disposition. He fully espoused the idea of transforming human consciousness through the kind of spiritual revolution that was the hallmark of the Russian Symbolists.

Although Lourié studied at the St Petersburg Conservatoire, where his composition teachers included Alexander Glazunov, his main musical influence in his youth was Alexander Scriabin, whose late piano works fascinated him. He was also greatly inspired by the Futurists, and he made musical settings of verses by poets such as Anna Akhmatova (with whom he conducted a passionate affair). Vladimir Mayakovsky and Alexander Blok affected him profoundly through the eloquence of their writing and the allure of their political views, which appealed to Lourié’s own radical disposition. He fully espoused the idea of transforming human consciousness through the kind of spiritual revolution that was the hallmark of the Russian Symbolists.  Finn Lykkebo began his musical education in earnest at the Royal Danish Academy of Music in 1960—initially as a church musician, and from 1963 onwards also with music theory and music history as principal subjects. He also studied composition under Per Nørgård, and at the same time Lykkebo composed choral settings, piano music and songs, primarily in smaller, more modest forms.

Finn Lykkebo began his musical education in earnest at the Royal Danish Academy of Music in 1960—initially as a church musician, and from 1963 onwards also with music theory and music history as principal subjects. He also studied composition under Per Nørgård, and at the same time Lykkebo composed choral settings, piano music and songs, primarily in smaller, more modest forms.  Among the artists who were to make their mark on the music scene in Yugoslavia during the mid-twentieth century, Ivo Macek occupies a significant place. Born in Sušak (now Croatia) on 24 March 1914, he trained at the Classical Gymnasium and also at the Music Academy in Zagreb. After graduation in 1934, he studied piano with Svetislav Stancic in Zagreb and composition with Jean Roger-Ducasse in Paris. Having taught at the Lisinki Music School in Zagreb and also holding the post of secretary at the Zagreb Opera, he quickly established himself as a pianist both in concert and in recital, giving performances across Yugoslavia and abroad—appearing with various established artists (such as the cellist Antonio Janigro and the cellist and conductor Enrico Mainardi) then, along with the cellist Mirko Dorner, winning the International Competition for Duo Performance at Vercelli in 1952. He had been the recipient of of a federal Government Award in 1948 and went on to win the Milka Trnina Award for concert performance in 1957–8, underlining his success both as performer and pedagogue.

Among the artists who were to make their mark on the music scene in Yugoslavia during the mid-twentieth century, Ivo Macek occupies a significant place. Born in Sušak (now Croatia) on 24 March 1914, he trained at the Classical Gymnasium and also at the Music Academy in Zagreb. After graduation in 1934, he studied piano with Svetislav Stancic in Zagreb and composition with Jean Roger-Ducasse in Paris. Having taught at the Lisinki Music School in Zagreb and also holding the post of secretary at the Zagreb Opera, he quickly established himself as a pianist both in concert and in recital, giving performances across Yugoslavia and abroad—appearing with various established artists (such as the cellist Antonio Janigro and the cellist and conductor Enrico Mainardi) then, along with the cellist Mirko Dorner, winning the International Competition for Duo Performance at Vercelli in 1952. He had been the recipient of of a federal Government Award in 1948 and went on to win the Milka Trnina Award for concert performance in 1957–8, underlining his success both as performer and pedagogue.  Nikolay Karlovich Medtner was Moscow born-and-bred, although his ancestry was German. As a child he showed musical promise, and studied piano with his mother until his acceptance into the Moscow Conservatory at the age of twelve. Medtner’s teachers during these years included Vasily Safonov for piano, Anton Arensky for harmony and Sergey Taneyev for counterpoint, the latter having a particularly strong influence on his musical development. Taneyev instilled in all his students a respect for the old masters—Palestrina, Bach, Mozart and especially Beethoven—and stressed contrapuntal and structural command as essential to any composer’s craft.

Nikolay Karlovich Medtner was Moscow born-and-bred, although his ancestry was German. As a child he showed musical promise, and studied piano with his mother until his acceptance into the Moscow Conservatory at the age of twelve. Medtner’s teachers during these years included Vasily Safonov for piano, Anton Arensky for harmony and Sergey Taneyev for counterpoint, the latter having a particularly strong influence on his musical development. Taneyev instilled in all his students a respect for the old masters—Palestrina, Bach, Mozart and especially Beethoven—and stressed contrapuntal and structural command as essential to any composer’s craft.  Alexander Vasilyevich Mosolov was born in Kiev in 1900, but moved with his family to Moscow three years later. When he was five, his father died, but his widowed mother, a professional singer who worked at the Bolshoi Theatre until 1905, was left comfortably well off. After her husband’s death, she married the painter and designer Michael W. Leblan (1875-1940). She cultivated a cosmopolitan outlook, and the young Alexander was brought up speaking French and German in addition to Russian. The family regularly visited the cultural capitals of western Europe, especially Paris, Berlin and London. During the October Revolution he volunteered to serve in the Red Army, but in 1921 he was medically discharged, suffering from what we would now call post-traumatic stress disorder. He then entered the Moscow Conservatoire and studied composition with Glière and Myaskovsky. In 1927 Prokofiev, who was then living in the West, returned for a concert tour of the Soviet Union. He became acquainted with the music of Mosolov, whom he praised as the most interesting of Russia’s new talents.

Alexander Vasilyevich Mosolov was born in Kiev in 1900, but moved with his family to Moscow three years later. When he was five, his father died, but his widowed mother, a professional singer who worked at the Bolshoi Theatre until 1905, was left comfortably well off. After her husband’s death, she married the painter and designer Michael W. Leblan (1875-1940). She cultivated a cosmopolitan outlook, and the young Alexander was brought up speaking French and German in addition to Russian. The family regularly visited the cultural capitals of western Europe, especially Paris, Berlin and London. During the October Revolution he volunteered to serve in the Red Army, but in 1921 he was medically discharged, suffering from what we would now call post-traumatic stress disorder. He then entered the Moscow Conservatoire and studied composition with Glière and Myaskovsky. In 1927 Prokofiev, who was then living in the West, returned for a concert tour of the Soviet Union. He became acquainted with the music of Mosolov, whom he praised as the most interesting of Russia’s new talents.  Christian Gottlob Neefe, born in 1748, is remembered today mainly as Beethoven’s first important teacher in Bonn. Neefe (pronounced Nay-fuh) was a respected and successful musician of his time: Court Organist and Kapellmeister of the Electoral Court Orchestra in Bonn, music director of a prominent theatre group, composer of numerous Singspiele (operettas) and other works, and music teacher. He became Beethoven’s teacher around 1780, in piano, organ, thoroughbass, and composition. A great admirer of the Bach family, he introduced Beethoven to the Well-Tempered Clavier of JS Bach, and the music and writings of Bach’s distinguished son, Carl Phillip Emanuel Bach. In addition, Neefe was a sympathetic and fatherly friend to the young Beethoven, who later wrote to him: “I thank you for the counsel which you gave me so often…If I ever become a great man yours shall be a share of the credit.”

Christian Gottlob Neefe, born in 1748, is remembered today mainly as Beethoven’s first important teacher in Bonn. Neefe (pronounced Nay-fuh) was a respected and successful musician of his time: Court Organist and Kapellmeister of the Electoral Court Orchestra in Bonn, music director of a prominent theatre group, composer of numerous Singspiele (operettas) and other works, and music teacher. He became Beethoven’s teacher around 1780, in piano, organ, thoroughbass, and composition. A great admirer of the Bach family, he introduced Beethoven to the Well-Tempered Clavier of JS Bach, and the music and writings of Bach’s distinguished son, Carl Phillip Emanuel Bach. In addition, Neefe was a sympathetic and fatherly friend to the young Beethoven, who later wrote to him: “I thank you for the counsel which you gave me so often…If I ever become a great man yours shall be a share of the credit.”  Dimitar Nenov was undoubtedly one of the leading figures in Bulgarian classical music from the first half of the twentieth century. A brilliant pianist, composer, and architect, he was a crucial figure for the generation of composers that came after him. It was this group of composers that formed the Bulgarian avant-garde of the 1950s and 1960s.

Dimitar Nenov was undoubtedly one of the leading figures in Bulgarian classical music from the first half of the twentieth century. A brilliant pianist, composer, and architect, he was a crucial figure for the generation of composers that came after him. It was this group of composers that formed the Bulgarian avant-garde of the 1950s and 1960s.  As well as a gifted pianist and composer Walter Niemann was a respected intellectual and author of numerous scholarly and literary works—the most renowned of which was Brahms, published in 1920 then translated into many languages. Meister des Klaviers: Die Pianisten der Gegenwart und der letzen Vergangenheit (Master of the Piano: Past and Present) was published in 1919 and was long considered a classic. He also wrote popular biographies of composers; that of Brahms emphasized the composer’s North German roots at the expense of his later Viennese years. As a reviewer he was often outspoken in his criticism of ‘pathological’ and ‘sensuous’ composers such as Richard Strauss, Mahler and Schoenberg, and was threatened in 1910 with a libel suit by Reger. Conversely, he praised nationalists and folk-influenced composers such as Pfitzner, Sibelius and MacDowell, and was influential in the popularizing of Scandinavian composers in Germany. Following the Second World War, Niemann’s idiom fell out of favour: he died largely neglected in Leipzig on 17 June 1953.

As well as a gifted pianist and composer Walter Niemann was a respected intellectual and author of numerous scholarly and literary works—the most renowned of which was Brahms, published in 1920 then translated into many languages. Meister des Klaviers: Die Pianisten der Gegenwart und der letzen Vergangenheit (Master of the Piano: Past and Present) was published in 1919 and was long considered a classic. He also wrote popular biographies of composers; that of Brahms emphasized the composer’s North German roots at the expense of his later Viennese years. As a reviewer he was often outspoken in his criticism of ‘pathological’ and ‘sensuous’ composers such as Richard Strauss, Mahler and Schoenberg, and was threatened in 1910 with a libel suit by Reger. Conversely, he praised nationalists and folk-influenced composers such as Pfitzner, Sibelius and MacDowell, and was influential in the popularizing of Scandinavian composers in Germany. Following the Second World War, Niemann’s idiom fell out of favour: he died largely neglected in Leipzig on 17 June 1953.  Per Nørgård is the most prominent Danish composer after Carl Nielsen. His signature can be found almost anywhere in Danish music as a result of his animation, teaching, thought-provoking theories and cultural criticism. For more than thirty years his widely embracing musical personality has inspired and influenced a host of Scandinavian composers.

Per Nørgård is the most prominent Danish composer after Carl Nielsen. His signature can be found almost anywhere in Danish music as a result of his animation, teaching, thought-provoking theories and cultural criticism. For more than thirty years his widely embracing musical personality has inspired and influenced a host of Scandinavian composers.  Oswald trained a generation of pianists and composers and became one of the most influential figures in Brazilian musical life in the first part of the present century.

Oswald trained a generation of pianists and composers and became one of the most influential figures in Brazilian musical life in the first part of the present century.  Manuel María Ponce was the author of a substantial and significant body of work and, as one of Mexico’s most prolific and well-known composers, is still held in great esteem today. His catalogue takes in virtually all genres and forms of music. One fundamental characteristic of his work is the use he made throughout his career of different styles, reflecting his range of knowledge and mastery of different compositional techniques. Broadly speaking, his music ranges from the post-Romanticism of the previous generation of composers to a modernism which made sporadic appearances in his early works but really began to establish itself in the music he wrote during his time in Paris (1925–33) and thereafter.