Boris Tchaikovsky (1925 - 1996)

In a career that spanned the last half of the twentieth Century, the composer Boris Tchaikovsky towered high among his Soviet contemporaries. His work received unalloyed praise from the most prominent musical figures, Shostakovich, Rostropovich, Kondrashin, Barshai, and Fedoseyev, and was represented on more than twenty Melodiya LPs, few of which circulated outside the Soviet Union. In the West, however, where musical tastes favoured the avant garde, his music was largely overlooked. That climate of opinion has been rapidly changing. As more of his work is recorded on CD, Boris Tchaikovsky is becoming widely recognised as one of the most important Russian composers of our time.

As both standard-bearer and innovator, Tchaikovsky arguably did more to enrich the tradition of Russian instrumental music than anyone else of his generation. He was trained at the Moscow Conservatory during the 1940s under Vissarion Shebalin, Shostakovich, and Nikolay Myaskovsky. He received his diploma in 1949, having studied with the leading instrumental composers of the time, Shostakovich, Nikolay Myaskovsky, and Vissarion Shebalin, bravely refusing to take part in the official condemnation of the much-abused Shostakovich. Tchaikovsky’s works from the 1940s and 1950s already display a pronounced gift for melody; his earliest compositions reflect an individual style.

Widely respected in Russia and praised by figures such as Shostakovich and Mstislav Rostropovich, Boris Tchaikovsky amassed a formidable body of works, including four symphonies, four instrumental concertos, six string quartets, a variety of chamber and orchestral music for various ensembles, piano and vocal music, and an abundance of music for the cinema.

His works from the 1950s, such as the celebrated Sinfonietta for Strings (1953), show that he was a traditionalist with forward-looking sensibilities. An extensive revamping of his style in the 1960s, coincident with the freer creative environment then emerging in the Soviet Union, led his music in fresh directions. Unlike the alienating rhetoric and the host of "isms" adopted by many of his contemporaries, Tchaikovsky's mature style maintained strong connections with its Russian roots. With its brittle lyricism, pronounced rhythmic features, and an expanded harmonic palette that never completely abandons tonality, the new style allowed him to take on a broad and at times exotic array of formal challenges. The result was a highly innovative, richly expressive body of work that appealed to a wide concert-going public.

The cultural thaw of the 1960s opened many doors for Soviet composers in an emerging freer creative environment. While some composers were drawn to avant-garde trends developed in the West, Tchaikovsky, quite independently, began to explore a bolder musical language of his own. Yet the lyricism that lies at the base of his musical thinking was undergoing profound metamorphosis. A fresh approach to composition was evolving whereby thematic development takes place as a kind of “mosaic” of accentuated, declamatory utterances. The striking rigidity of these utterances, a Tchaikovsky hallmark, and their strong rhythmic characteristics are related to similar aspects found in Russian folk-music. They somehow impart to his music a distinctly Russian sound while completely avoiding any traces of an overt folk influence. A corresponding increase in the level of dissonance and the use of bolder orchestral colours are also to be noted. What in fact Tchaikovsky had created was a highly personal, thoroughly up-to-date musical language capable, as will be apparent, of an astonishingly wide range of expression. Tchaikovsky’s new style opened up a world of formal exploration and expressivity, mostly in the realm of abstract instrumental music. Technical challenges of one sort or another fascinated him and led to an ever-fresh source of inspiration.

His most daring compositions include a bravura Cello Concerto (1964) that challenges the notion of thematic identity, a single-movement Violin Concerto (1969) that shuns the time-honoured musical practice of repetition, and a five-movement Piano Concerto (1971) all of whose elements derive from primitive rhythmic patterns. His orchestral compositions, such as his Theme and Eight Variations (1973) and the tone-poems Wind of Siberia and Juvenile (both of 1984), reveal a wealth of lyrical invention. His symphonies embrace an ever-expanding quest for innovation within traditional forms. To briefly summarise, in the First Symphony (1947) matters of thematic organization receive individual treatment; the Second Symphony (1967) incorporates musical quotations from the classics as points of structural departure; the Third Symphony, "Sebastopol", (1980) is conceived as a single monumental movement; and his Symphony with Harp (1993) explores a unique set of timbral possibilities.

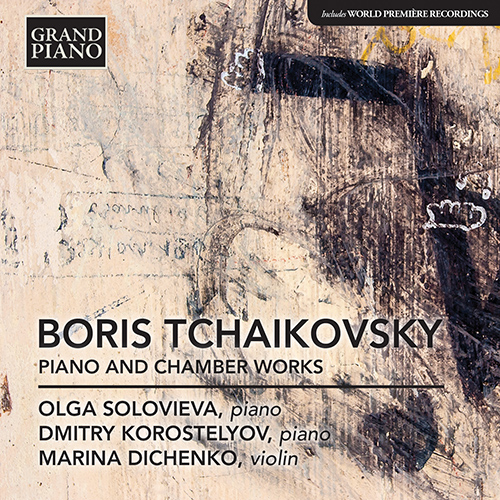

Grand Piano has gained a reputation for producing high quality recordings of rare keyboard gems. Dedicated to the exploration of undiscovered piano repertoire, the label specialises in complete cycles of piano works by many lesser-known composers, whose output might otherwise have remained unknown and unrecorded.

Grand Piano has gained a reputation for producing high quality recordings of rare keyboard gems. Dedicated to the exploration of undiscovered piano repertoire, the label specialises in complete cycles of piano works by many lesser-known composers, whose output might otherwise have remained unknown and unrecorded.