Maria Szymanowska (1789 - 1831)

The young Maria Wolowska displayed extraordinary musical precocity and she quickly became a sensation in the Warsaw salons. To broaden her musical horizons, it was decided to send her to Paris, where her fame spread. There she impressed such luminaries as the composers Gioachino Rossini and Luigi Cherubini (who dedicated a piano fantasia to her).

After her return to Poland in 1810 she married Józef Szymanowski, a wealthy landowner, and before long there were three children (one of whom, Celina, later married Adam Mickiewicz, Poland’s national poet). The Szymanowskis’ marriage was not successful and it ended in divorce in 1820. Maria (who retained her married name for professional purposes) resumed her international career in 1815 and undertook some very long tours that included both private and public performances. It was during an arduous three-year tour of western Europe between 1823 and 1826 that she first met Goethe. She also had an audience with the British royal family, and in 1828 travelled to Russia, where she was employed by the imperial court as First Pianist to the empress. During the summer of 1831 Maria Szymanowska succumbed to a cholera epidemic that swept St Petersburg, and she died on 25 July, aged 41.

Through her own compositions, which appealed to professionals and amateurs alike, Szymanowska played an important part in the early development of that quintessentially Romantic musical phenomenon: the pianist-composer. She was greatly admired by her contemporaries, and her recitals routinely included works by living composers such as Hummel and Beethoven (whose Bagatelle in B flat, WoO 60, is dedicated to her). The influential Czech composer and teacher Václav Tomášek, who counted Beethoven and Goethe among his acquaintances, praised the clarity and attack of Szymanowska’s keyboard technique, and he also wrote enthusiastically of her inspirational performance style.

By the end of the nineteenth century salon music had become strongly associated with dilettantism and mass consumerism, but in earlier decades its defining characteristics were elegance and refinement. These qualities are admirably displayed in Szymanowska’s attractive collections of dances, which include polonaises, waltzes, mazurkas, quadrilles and contredanses (in addition to more unusual types such as cotillions and anglaises). Taken collectively, these dances are, for the most part, pleasing and light, with precisely the degree of imaginative artistic inventiveness needed to appeal to the aristocratic salons of the day.

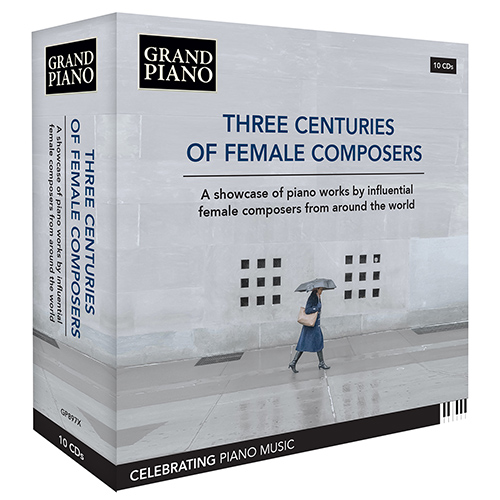

Grand Piano has gained a reputation for producing high quality recordings of rare keyboard gems. Dedicated to the exploration of undiscovered piano repertoire, the label specialises in complete cycles of piano works by many lesser-known composers, whose output might otherwise have remained unknown and unrecorded.

Grand Piano has gained a reputation for producing high quality recordings of rare keyboard gems. Dedicated to the exploration of undiscovered piano repertoire, the label specialises in complete cycles of piano works by many lesser-known composers, whose output might otherwise have remained unknown and unrecorded.