Johann Baptist Vaňhal (1739 - 1813)

The public perception of Johann Baptist Wanhal has changed little since his death in 1813. The biographical articles in Die Musik in Geschichte und Gegenwart (1951) and The New Grove (1980), both written by the same author, were based upon the identical early 19th-century authors. So too were all incidental articles written subsequent to Wanhals death. They reflect the questionable comprehension and biases of the original authors: Dr Charles Burney, whose single visit with Wanhal occurred in 1772, Gottfried Johann Dlabacz, his Bohemian compatriot who stayed with him in Vienna for some time in 1795, and an anonymous Viennese author whose necrology seems to have been mostly based upon rumour and filtered through the interpretations of authors such as Gerber and Rochlitz. The following presents my own interpretation based upon rereading the sources in the light of recent investigations of the Viennese musical scene. Detailed discussion, including my reasons for spelling his name with a "W", may be found in my book, Johann Wanhal, Viennese Symphonist, His Life and His Musical Environment, published by Pendragon Press in 1997.

Wanhals life may be divided into five periods. The first lasted from his birth as a bonded servant on 12 May 1739 in the Bohemian village of Nechanicz until he moved to Vienna to begin his career in 1760 or 1761. During these twenty years he received excellent training from fine teachers in several Bohemian towns and villages so that he became an accomplished violinist and organist, and a composer of both instrumental and church music. At the same time he prepared himself for a move to Vienna by learning to speak German. His attractive personal characteristics (happy, modest, honest, personal warmth, good looks, personal deportment, deeply religious, etc.) together with his pragmatic and independent spirit foretold his later success.

The second period of Wanhals life began when the Countess Schaffgotsch, to whose family he was in bondage, offered to take him to Vienna. The exact date is not ascertainable, but it was fortunate because he arrived at a crucial time in the history of instrumental music. It was the beginning of an approximately twenty-year period (1760s - early 1780s) when, supported by the exhilaration of a booming economy, the nobility in Vienna were competing with each other and the newly rich burgers for the prestige derived from having the most glamorous musical soirees - with new music performed by their own orchestras. It also coincided with the tempestuous rise of the printed-music industry in Paris that reflected the massive upsurge of interest in music that was sweeping Europe. Wanhal was quickly accepted into the centre of the activity as a violinist, composer and teacher. Problems of authenticity and dating negate any attempt to be absolutely accurate, but I estimate that during the first nine or so years he composed more than thirty symphonies along with chamber music, and music for the church. The competition between those who wanted to have their own orchestras during the opulent decade of the 1760s dictated that Kapellmeister were needed who could recruit and train musicians, provide music for them to play, care for the practical aspects of an orchestra, such as managing the affairs of the personnel, arrange performances, etc. That Wanhal possessed all the essential musical and personal qualities was recognized by Baron Issac von Riesch of Dresden, who wanted to establish his own Kapelle. He accordingly persuaded Wanhal to accept his financial support and go to Italy - which was considered a kind of finishing school - where he could spend a substantial period of time rubbing elbows with the leading musicians, writers and intelligentsia - and thus acquire the final polish necessary for the leader of a Kapelle.

May 1769 to September 1770 demark the third period of Wanhals life, which was spent in various Italian cities (especially Florence). His association with many famous persons included leading composers such as Gluck. He also met the great social reformer, Emperor Joseph II, an encounter that I believe had special significance since Wanhal had, in the previous decade in Vienna, been able to buy his freedom from the bondage inherited from his birth in Bohemia. During this same period he was also able to contemplate the heavy demands of the position in Dresden for which he was being groomed - and be evermore aware of his enormous debt to Baron Riesch.

At the outset of the third period in 1770, Wanhals return from Italy put him in the awkward position of being obligated to accept a position that he did not desire. Nonetheless, his utilitarian and independent nature caused him to refuse the position. There are no accounts of what transpired, but the embarrassment and notoriety must have been very unpleasant, and he was depressed for some time. Furthermore, he found himself with only the support he could derive from teaching and composing - his situation when Burney visited him in 1772.

During the following years he was several times (from 1773 to 1779) invited by Count Ladislaus Erddy, one of the great patrons of musicians, to his estate in Varazdin, Croatia. There are no records of when or how often these visits occurred, other than a few dates found on several works composed for the nuns in a convent in Varazdin. However, the music Wanhal produced in Vienna and published in Paris in the 1770s bears witness to his constant activity on the musical scene. The gradual increase in his published compositions shows that he was successful in supporting himself, but there were changes in the genre of music he wrote and published. As the robust economic conditions in Vienna declined during the later 1770s so did the fad for orchestral soirees. Wanhals last symphonies were published in Berlin ca. 1780, and soon thereafter a reviewer in Hamburg expressed hope that Wanhal would continue to compose symphonies. But the market for symphonies in Vienna was rapidly diminishing, and the practical Wanhal composed no more of them.

The beginning of the fifth and final period of Wanhals life is less clearly definable, but by 1785 he was ensconced on the Viennese scene. By this time the Viennese publishers had seized the initiative from the French publishers who had for many years provided them with prints, even of their own composers, including Wanhal. Publishers such as Artaria, Hoffmeister, and Sauer were fiercely competing in response to the demands of a new musical public whose tastes had changed, away from symphonies to small groups, Harmoniemusik, solo and instructional-pieces for keyboard, and programmatic pieces.

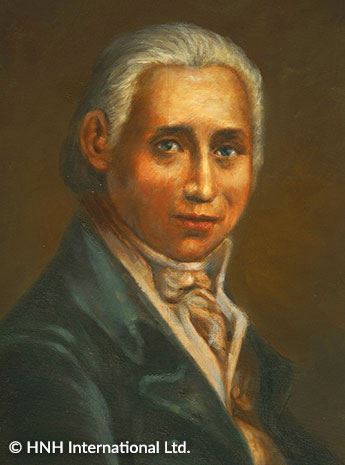

A few reports from 1784 and 1787 place Wanhal in Viennese society, but in general he seems to have been gradually retreating from active public life. By 1795, however, when Dlabacz visited him in Vienna, Wanhal was prospering, as may be seen in an oil painting in the possession of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna (See the frontispiece of my book). He apparently lived in comfortable circumstances for the remainder of his life. His death records show that he was living in an apartment close to St Stephans Cathedral in Vienna, incidentally close to his most active publishers, and that his modest possessions were willed to the wife (widow?) of a Viennese bookseller.

In retrospect, a special legacy from him also deserves recognition. Through his strength of will and character he broke fee of his bondage and consciously shunned the support of a patron. Thus, when he refused to accept Baron Rieschs position in 1770 he became one of the first active participants in the new social order. He created his own peaceful Viennese version of the French Revolution.

Paul Bryan

Grand Piano has gained a reputation for producing high quality recordings of rare keyboard gems. Dedicated to the exploration of undiscovered piano repertoire, the label specialises in complete cycles of piano works by many lesser-known composers, whose output might otherwise have remained unknown and unrecorded.

Grand Piano has gained a reputation for producing high quality recordings of rare keyboard gems. Dedicated to the exploration of undiscovered piano repertoire, the label specialises in complete cycles of piano works by many lesser-known composers, whose output might otherwise have remained unknown and unrecorded.