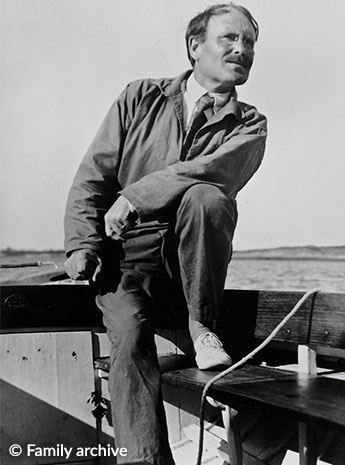

Paul Le Flem (1881 - 1984)

In what was, regrettably, an interrupted career as a composer, Paul Le Flem always maintained his deeply-rooted aesthetic convictions, and yet also successfully adapted his musical idiom to suit the modern innovations of the day.

Like his older colleagues Guy Ropartz and Louis Aubert, he was of Breton origin, and once recalled: “The first music I heard was the folk songs of Brittany, which were very beautiful—they seduced me, lit the flame of love within me…” That Breton soundworld of his childhood was soon broadened and enriched when he began to teach himself harmony and music theory. He went to his first concerts and opera performances in Brest, and started composing before he sat his baccalauréat exams in 1899. Like Albert Roussel a few years earlier, Le Flem heard the call of the sea and planned to study at the École Navale, but in the event, his poor eyesight meant a maritime career was out of the question. Instead he went to Paris, studying with Lavignac at the Conservatoire—where the academic teaching style failed to enthuse him—as well as graduating in philosophy from the Sorbonne.

In 1902, he attended the earliest performances of Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande, its harmonic idiom imprinting itself indelibly on his imagination. That summer, he left for Russia, where he spent the next eighteen months as a private tutor and also acquired a sound knowledge of the Russian language.

On his return to Paris, he decided to pick up his music studies again, but this time at the Schola Cantorum with Vincent d’Indy (composition) and Albert Roussel (counterpoint). He also studied the polyphonists of the Renaissance, an area of interest he shared with his friend and fellow student Edgar Varèse.

Le Flem was later to say, “It may seem strange that, having studied with Vincent d’Indy, I then chose to follow more closely in the footsteps of Claude Debussy. I think what really attracted me to his music was its intense poetry, which reminded me of the poetry of the folk songs that had shaped my childhood. I could suggest that Debussy’s poetics and D’Indy’s strict sense of order were two opposing extremes, but the truth is that both of them have left a mark on my work, which has been inspired by a fusion of three influences: my native Brittany, Debussy and D’Indy.”

The years leading up to the First World War gave an indication of the way Le Flem’s career would develop in the interwar period, as he began to divide his time between teaching, criticism and choral conducting. His teaching skills were soon noted by others: in a letter to Roland-Manuel on 14th September 1911, Erik Satie, then a mature student at the Schola Cantorum, wrote “Roussel isn’t taking the class until December. His replacement is Le Flem, who is doing a very good job.”

As a critic, he championed the boldest new works of his time, his reviews always well informed and soundly argued. Despite his D’Indyist training, when he attended the première of Debussy’s ballet Jeux in 1913, he praised the sophistication of its “music with broken rhythms, well suited to a variable choreography”.

His own compositional career was interrupted by the outbreak of war.

Arthur Honegger was later to remark that, “On the eve of 1914, Paul Le Flem was one of the leading “musicians of tomorrow”, but he voluntarily stepped aside to make room for the new “musicians of today”.” He realised, for example, that one of his students, André Jolivet, would benefit from working with Varèse, and duly made the introduction.

Le Flem only switched his focus back to composing in 1937. As well as stage works linked to the tales and legends of his native Brittany such as Le Rossignol de Saint-Malo (The nightingale of Saint-Malo, 1938) and La Magicienne de la mer (The sorceress of the sea, 1947), he also produced more abstract works such as the Concertstück for violin (1965) and three symphonies (1957, 1972, 1974) which demonstrate how his musical idiom was developing towards atonality.

His catalogue of works for piano is dominated by four pieces inspired by Brittany, all of them steeped in the region’s landscapes and ever-changing seascape, its light, its climate, its vegetation, its austere granitic geology and its traditional mysteries and legends, in all their tonal variety, from the lighthearted to the disquieting.

Grand Piano has gained a reputation for producing high quality recordings of rare keyboard gems. Dedicated to the exploration of undiscovered piano repertoire, the label specialises in complete cycles of piano works by many lesser-known composers, whose output might otherwise have remained unknown and unrecorded.

Grand Piano has gained a reputation for producing high quality recordings of rare keyboard gems. Dedicated to the exploration of undiscovered piano repertoire, the label specialises in complete cycles of piano works by many lesser-known composers, whose output might otherwise have remained unknown and unrecorded.