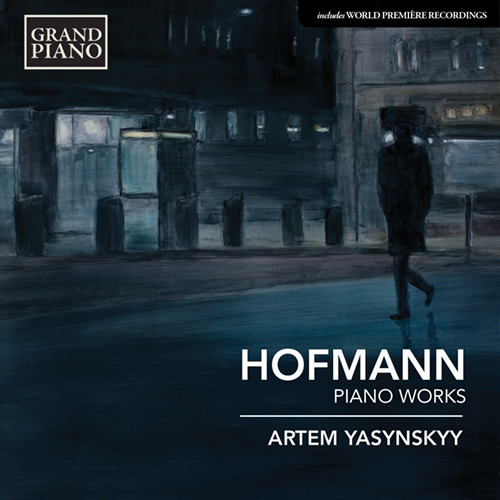

Józef Hofmann (1876 - 1957)

Józef (Josef) Hofmann was born near Kraków in 1876. His parents were both professional musicians, and with their encouragement he gave his first recital at the tender age of five. Needless to say, extremely flattering comparisons were made between his prodigious abilities and those of the young Mozart and Mendelssohn. When Anton Rubinstein (himself a former child prodigy) heard the seven-year old Józef play Beethoven’s C minor Concerto in Warsaw, he remarked on the boy’s unprecedented talent.

Hofmann’s playing was considered noble and poetic, free from any eccentricity, and never routine. In a recent article for The Daily Telegraph, Stephen Hough wrote: ‘Hofmann’s assertive brilliance was breathtaking…and new’. He concludes that ‘no one had ever played like this before, and I think it’s the main reason he was crowned king at a time of many princes.’

Hofmann was the first artist of note to record, and his legacy of piano rolls and gramophone records means that modern audiences can still appreciate the playing of this king of the Golden Age. He made some experimental cylinder recordings for Thomas Edison in 1887 when he was eleven, and even at that age he was fascinated by the technical aspects of the nascent recording industry. His first commercial recordings were made in Berlin in 1903. Highlights of his early recording career include the Prelude in G minor, Op 23, No 5, by his friend Rachmaninov, who dedicated his Piano Concerto No 3 to Hofmann.

Like so many other performing artists of the past, Hofmann was equally at home composing. His output includes a symphony, five piano concertos and a considerable quantity of solo piano music. Some of his smaller pieces appeared under the pseudonym Dvorsky (which is actually the Polish equivalent of Hofmann). He delighted in the fiction that Michel Dvorsky was a reclusive young Frenchman who modestly sent his efforts to Hofmann for evaluation. The humour behind this innocent little deceit is akin to that of the violinist Fritz Kreisler, who famously ascribed the names of little-known composers to some of his own slighter pieces.

Hofmann’s compositions are positioned very firmly in the Romantic tradition. To his contemporaries, familiar with the recent work of Debussy or Scriabin, they probably came across as old-fashioned, but now that sufficient time has passed we can simply enjoy the music on its own terms without worrying about whether it is ‘modern’ enough.

Grand Piano has gained a reputation for producing high quality recordings of rare keyboard gems. Dedicated to the exploration of undiscovered piano repertoire, the label specialises in complete cycles of piano works by many lesser-known composers, whose output might otherwise have remained unknown and unrecorded.

Grand Piano has gained a reputation for producing high quality recordings of rare keyboard gems. Dedicated to the exploration of undiscovered piano repertoire, the label specialises in complete cycles of piano works by many lesser-known composers, whose output might otherwise have remained unknown and unrecorded.