Anne-Louise Boyvin d'Hardancourt Brillon de Jouy (1744 - 1824)

Cultured, refined and highly intelligent, she married a local man 22 years her senior, Jacques Brillon de Jouy and, as a submissive and well-brought-up young wife, she established a home like the one she had known as a child. In the Brillon household, painting and music played a key role, and the couple made sure that their two daughters, Cunégonde and Aldegonde, were also instructed in music, especially singing. Soon Anne-Louise Brillon de Jouy was holding salons, where musicians of the period like the violinist Jean-Pierre Pagin and cellist Luigi Boccherini rubbed shoulders.

These salons, known as ‘intellectual gatherings’, brought together artists, intellectuals, philosophers and the whole of 18th-century bourgeois society. Music played a central part in the one hosted by Madame Brillon. Being a talented harpsichord player herself, she entertained musicians and acted as their accompanist. Since she had a keen interest in contemporary music, it is conceivable that some works received their first performance in this setting. As someone who was resolutely modern in her outlook, it is no surprise that she acquired a fortepiano for her salon.

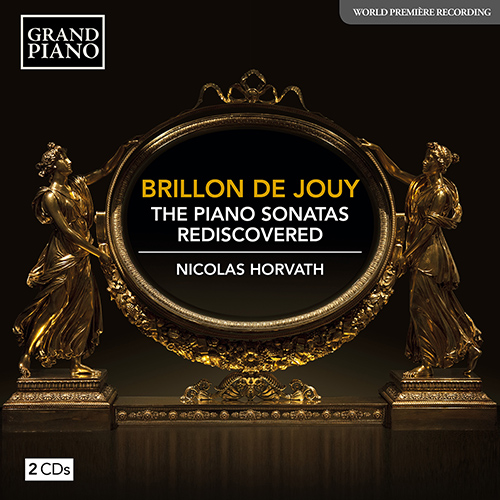

In addition to her gifts as an instrumentalist, Madame Brillon also composed. She has almost 90 works to her credit, most of them chamber music. She wrote for keyboard, but also composed sonatas for cello, violin or harp, trios, and sometimes vocal music which one can imagine her two daughters performing. Her music was only played in private settings, in particular at her own salons. None of her works were published during her lifetime. This is not an oversight but a choice: at that time, it was not the done thing for a woman of Anne-Louise’s standing to make her music public. Composition and playing music had to be reserved for the private sphere.

When Benjamin Franklin arrived in Paris, he moved into the house next door to the Brillons. Anne-Louise and the future president of the United States were to maintain a close friendship for the rest of their lives. In his correspondence, Benjamin Franklin described the salon of his beloved neighbour as ‘my Opera’, where there are ‘little Concerts’ with music and singing. The Revolution put an end to these salons. Madame Brillon needed to survive, rescue her furniture, support her family, and deal with the turmoil after losing several of her grandchildren. She divided her time between Paris and her brother-in-law’s château at Villers in Normandy. Music continued to have a special place in her life right to the end.

Anne-Louise Brillon de Jouy died in Villers on 5 December 1824. She was 80.

Aliette de Laleu

Translation: Susan Baxter

Grand Piano has gained a reputation for producing high quality recordings of rare keyboard gems. Dedicated to the exploration of undiscovered piano repertoire, the label specialises in complete cycles of piano works by many lesser-known composers, whose output might otherwise have remained unknown and unrecorded.

Grand Piano has gained a reputation for producing high quality recordings of rare keyboard gems. Dedicated to the exploration of undiscovered piano repertoire, the label specialises in complete cycles of piano works by many lesser-known composers, whose output might otherwise have remained unknown and unrecorded.