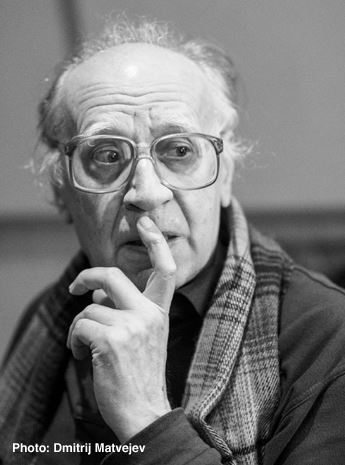

Valentin Silvestrov (b.1937)

Valentin Silvestrov was born on 30 September 1937 in Kiev. He came to music relatively late, at the age of fifteen, and was initially self-taught. From 1955 to 1958 he took courses at an evening music school while training to become a civil engineer: from 1958 to 1964 he studied composition and counterpoint, respectively, with Boris Lyatoshinsky and Lev Revutsky at Kiev Conservatory. He then taught at a music studio for several years. He has been a freelance composer in Kiev since 1970.

Silvestrov is considered one of the leading representatives of the “Kiev avant-garde”, which came to public attention around 1960 and was violently criticized by the proponents of the conservative Soviet musical aesthetic. In the 1960s and 1970s his music was hardly played in his native city; premieres, if given at all, were heard only in Russia, primarily in Leningrad (now St. Petersburg), or in the West. His Spectrums for chamber orchestra, for example, was premiered to spectacular acclaim by the Leningrad Philharmonic under the baton of Igor Blashkov in 1965. In 1968 the same conductor gave the premiere of the Second Symphony.

The works of the young composer were awarded the Koussevitzky Prize in 1967, and the Hymn for Six Orchestral Groups earned Silvestrov the festival’s honorary title of 1970.

Despite these successful performances in the West (the composer himself was not allowed to attend them!), Silvestrov’s music met with no response in his own country and tended to remain “sub rosa.” The avant-gardist tag created obstacles at every turn. For a long time his works were at least heard on the periphery of the official music scene, thanks to the enthusiasm of some performers.

This situation gradually changed with Silvestrov’s growing international acclaim. One of his earliest champions was the American pianist and conductor Virko Baley, an aficionado and longtime advocate of contemporary Ukrainian music in general and Silvestrov’s works in particular. It was Baley who brought about the Las Vegas performances of Postludium for piano and orchestra (1985) and the symphony Exegi monumentum (1988) as well as a Valentin Silvestrov 50th Birthday Concert in New York (1988). Silvestrov became a visiting composer at the Almeida Music Festival in London (1989), Gidon Kremer’s Lockenhaus Festival in Austria (1990), and various festivals in Denmark, Finland, and Holland.

Since the end of the 1980s, the number of performances has increased, even in Russia and the Ukraine. Silvestrov’s music was heard at the “Alternative” New Music Festival in Moscow (1989), “Five Evenings with the Music of Valentin Silvestrov” (Ekaterinburg, 1992), “Sofia Gubaidulina and Her Friends” (St. Petersburg, 1994), “Sofia Gubaidulina, Arvo Part, Valentin Silvestrov” (Moscow, 1995), and the Silvestrov 60th Birthday Festival (Kiev, 1998). At the latter event, a scholarly conference devoted to Silvestrov was held at the Tchaikovsky National Academy of Music of the Ukraine (formerly Kiev Conservatory).

During the 1990s, Silvestrov’s music was heard throughout Europe as well as in Japan and the United States. In 1998–9, he was a visiting fellow of the German Academic Exchange Service in Berlin, where three of his works have been premiered to date: Metamusic (March 1993), Dedication for violin and orchestra (November 1993), and the Sixth Symphony (August 2002).

Both in his earlier avant-garde period and after his stylistic volte-face of 1970, Silvestrov has preserved his independence of outlook. In recent decades he has dispensed with the conventional compositional devices of the avant-garde and discovered a style comparable to western “post-modernism”. The name he has given to this style is “metamusic”, a shortened form of “metaphorical music”.

Of all the many translations of the Greek combinative particle meta (post-, supra-, ultra-, extra-, etc.) Silvestrov prefers “supra” or “ultra”. He regards metamusic as “a semantic overtone on music”. In a certain sense, “metamusic” is also a synonym for a universal style (a concept that Silvestrov has been using for some time) and a universal language. He understands it to mean “a general ‘lexicon’ that belongs to no one but can be used by anyone in his or her own way”. His work has affinities with the age of the “classical” fin-de-siecle, especially Gustav Mahler, with whom Silvestrov is often compared. The difference is that the lexicon of today is unlimited. This limitlessness forces composers to search for the lost ontological meaning of music as art. In Silvestrov’s view a view that reveals the lyric basis of his art regardless of the period in his career one of the crucial prerequisites for the continued existence of music resides in melody, which he also regards in an expanded sense of the term. This has found expression in the remarkable role that vocal music has played in his musical output. Silvestrov is the author of two large and many shorter song cycles in addition to isolated songs and cantatas, usually on poems by classical authors. In his relation to poetry, he avoids trying to disturb the music inherent in the poems themselves and attempts to subordinate himself to it. “Poetry...is the salvaging of all that is most essential, namely, melody as a holistic and inalienable organism. Either this organism is there, or it is not. For it seems to me that music is song in spite of everything, even when it is unable to sing in a literal sense. Not a philosophy, not a system of beliefs, but the song of the world about itself, and at the same time a musical testament to existence.” This same approach also governs Silvestrov’s instrumental music, which is always richly infused with both logical and melodic tension.

Listen to FROM RUSSIA WITH LOVE: RUSSIAN PIANO MUSIC on Spotify

Grand Piano has gained a reputation for producing high quality recordings of rare keyboard gems. Dedicated to the exploration of undiscovered piano repertoire, the label specialises in complete cycles of piano works by many lesser-known composers, whose output might otherwise have remained unknown and unrecorded.

Grand Piano has gained a reputation for producing high quality recordings of rare keyboard gems. Dedicated to the exploration of undiscovered piano repertoire, the label specialises in complete cycles of piano works by many lesser-known composers, whose output might otherwise have remained unknown and unrecorded.