About this Release

- Reinhold Glière

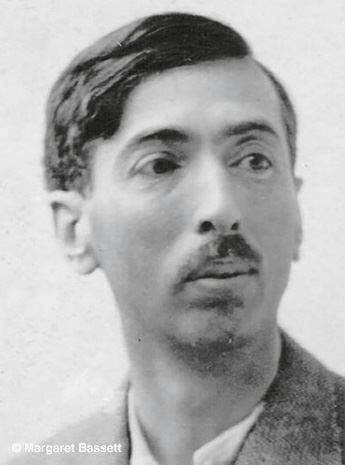

- Tibor Harsányi

- Mihail Jora

- Klimenty Arkad'yevich Korchmaryov

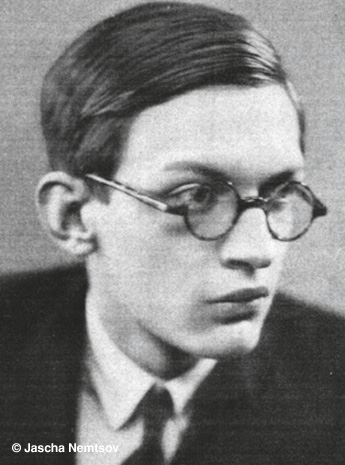

- Yulian Krein

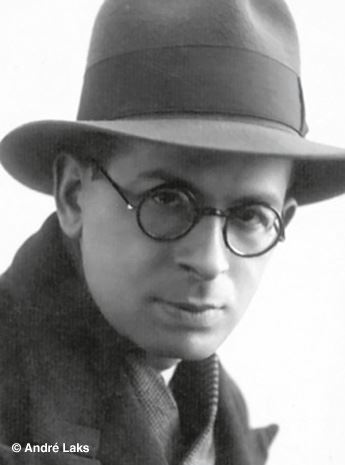

- Simon Laks

- Aleksandr Levin

- Mihovil Logar

- Alexander Moyzes

- Yevgeny Mravinsky

- Dora Pejačević

- Leonid Alekseyevich Polovinkin

- Dmitry Shostakovich

- Mischa Spoliansky

- Alexandre Tansman

- Ivo Tijardović

- Dimitri Tiomkin

- Alexander Tsfasman

- Pancho Vladigerov

- Eugene Zádor

“There was a period in the Twenties, now one hundred years ago, where all the world started to dance the same happy dances. Everywhere gramophones and radios brought the voice of America, its fashion, its carelessness, its joy of living. No composer could remain immune to a certain jazz influence and Eastern Europe was no exception. The third volume of my anthology of Jazz-influenced piano music features composers from no less than nine Central and Eastern European countries. One of my highlights of this volume is Misha Spoliansky’s hypnotizing Valse Boston ‘Morphium’. In stark contrast, Leonid Polovinkin’s futuristic approach to Foxtrot and Tango is extremely entertaining and refreshing to our ears. Listen up!” — Gottlieb Wallisch

20TH CENTURY FOXTROTS • 3

Central and Eastern Europe

- Gottlieb Wallisch, piano

Gramophones and radios brought the voice of America, its fashion, its carelessness and joie de vivre into every corner of Europe during the Roaring Twenties, and no composer could remain immune to the hot jazz influences of the Foxtrot, Shimmy and Charleston. This third volume of jazzy piano dances features composers from nine Central and Eastern European countries, from Misha Spoliansky’s hypnotising Valse Boston ‘Morphium’ to Leonid Polovinkin’s extremely entertaining and refreshingly futuristic approach to the genre. Gottlieb Wallisch continues his ‘most surprising and consistently charming recording project’ (The New York Times on Volume 2, GP814).

This recording was made on a modern instrument: Steinway, Model D

Tracklist

|

Pejačević, Dora

|

|

1

Vertige, Valse-Boston (1906) (00:03:22)

|

|

Tijardović, Ivo

|

|

2

Mein Shimmy, Jazz Band Shimmy (1922) (00:01:53)

|

|

3

Loulou la languide, Foxtrot (1921) (00:02:43)

|

|

Logar, Mihovil

|

|

4

Tango-Berceuse (1933) (00:02:31)

|

|

Vladigerov, Pancho

|

|

5

Foxtrot () (00:03:47)

|

|

Jora, Mihail

|

|

6

Joujoux pour ma dame, Op. 7: III. Un Fox-trott pour ma dame (1925) (00:01:42)

|

|

Harsányi, Tibor

|

|

7

Vocalise-étude, "Blues" (version for piano) (1929) (00:02:32)

|

|

8

13 Danses: Fox-Trot (1929) (00:01:49)

|

|

Zádor, Eugene

|

|

Bagatellen in Jazz (1931) (00:05:00 )

|

|

9

No. 1. Andantino (00:03:22)

|

|

10

No. 2. Vivace (00:01:18)

|

|

Moyzes, Alexander

|

|

11

Divertimento, Op. 11: IV. Tango-Blues (version for piano) (1930) (00:01:58)

|

|

Spoliansky, Mischa

|

|

12

Jimmy Shimmy (1921) (00:02:02)

|

|

13

Morphium, Valse Boston (version for piano) (1920) (00:03:54)

|

|

14

Harlem Blues (pre-1943) (00:02:10)

|

|

Tansman, Alexandre

|

|

15

Symphony No. 3, "Symphonie concertante": II. Tempo americano (version for piano) (1931) (00:04:27)

|

|

Laks, Simon

|

|

16

Blues () (00:04:02)

|

|

Mravinsky, Yevgeny

|

|

17

Fox-Trot (1929) (00:01:55)

|

|

Levin, Aleksandr

|

|

18

Valse Boston, Op. 15 (1926) (00:04:33)

|

|

Shostakovich, Dmitry

|

|

19

Klop (The Bedbug), Op. 19: Foxtrot (version for piano) (1929) (00:01:42)

|

|

20

Zolotoy vek (The Golden Age), Op. 22, Act I Scene 2: Foxtrot… Foxtrot… Foxtrot… (version for piano) (1930) (00:04:41)

|

|

Krein, Yulian

|

|

21

Tango (1930) (00:05:40)

|

|

Polovinkin, Leonid Alekseyevich

|

|

22

Fox-trot, "Ski" (1925) (00:02:36)

|

|

23

3 South-American Dances: No. 2. Tango () (00:02:28)

|

|

Glière, Reinhold

|

|

24

The Red Poppy, Op. 70, Act III: Charleston (version for piano) (1927) (00:02:21)

|

|

Korchmaryov, Klimenty Arkad'yevich

|

|

25

American (1928) (00:02:24)

|

|

Tiomkin, Dimitri

|

|

26

Créoles blues (original version for piano) (1927) (00:02:56)

|

|

Tsfasman, Alexander

|

|

27

I Want to Dance, Foxtrot (1957) (00:01:13)

|

|

28

Lyrical Rumba (c. 1950) (00:02:22)

|

The Artist(s)

Born in Vienna, Gottlieb Wallisch first appeared on the concert platform when he was seven years old, and at the age of twelve made his debut in the Golden Hall of the Vienna Musikverein. A concert directed by Yehudi Menuhin in 1996 launched Wallisch’s international career: accompanied by the Sinfonia Varsovia, the seventeen-year-old pianist performed Beethoven’s ‘Emperor’ Concerto.

Since then Wallisch has received invitations to the world’s most prestigious concert halls and festivals including Carnegie Hall in New York, Wigmore Hall in London, the Cologne Philharmonie, the Tonhalle Zurich, the NCPA in Beijing, the Ruhr Piano Festival, the Beethovenfest in Bonn, the Festivals of Lucerne and Salzburg, December Nights in Moscow, and the Singapore Arts Festival. Conductors with whom he has performed as a soloist include Giuseppe Sinopoli, Sir Neville Marriner, Dennis Russell Davies, Kirill Petrenko, Louis Langrée, Lawrence Foster, Christopher Hogwood, Martin Haselböck and Bruno Weil.

Orchestras he has performed with include the Vienna Philharmonic and Vienna Symphony Orchestras, the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, the Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra, the Frankfurt Radio Symphony, the Festival Strings Lucerne, the Franz Liszt Chamber Orchestra in Budapest, the Musica Angelica Baroque Orchestra in Los Angeles, and the Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra.

Born in Vienna, Gottlieb Wallisch first appeared on the concert platform when he was seven years old, and at the age of twelve made his debut in the Golden Hall of the Vienna Musikverein. A concert directed by Yehudi Menuhin in 1996 launched Wallisch’s international career: accompanied by the Sinfonia Varsovia, the seventeen-year-old pianist performed Beethoven’s ‘Emperor’ Concerto.

Since then Wallisch has received invitations to the world’s most prestigious concert halls and festivals including Carnegie Hall in New York, Wigmore Hall in London, the Cologne Philharmonie, the Tonhalle Zurich, the NCPA in Beijing, the Ruhr Piano Festival, the Beethovenfest in Bonn, the Festivals of Lucerne and Salzburg, December Nights in Moscow, and the Singapore Arts Festival. Conductors with whom he has performed as a soloist include Giuseppe Sinopoli, Sir Neville Marriner, Dennis Russell Davies, Kirill Petrenko, Louis Langrée, Lawrence Foster, Christopher Hogwood, Martin Haselböck and Bruno Weil.

Orchestras he has performed with include the Vienna Philharmonic and Vienna Symphony Orchestras, the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, the Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra, the Frankfurt Radio Symphony, the Festival Strings Lucerne, the Franz Liszt Chamber Orchestra in Budapest, the Musica Angelica Baroque Orchestra in Los Angeles, and the Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra. The Composer(s)

Hungarian-born pianist, composer, conductor, and musicologist Tibor Harsányi was part of the lively Paris musical scene from 1923. He was a student of Kodály in Budapest, then travelled around Europe as a performer, settling briefly in Holland, where he worked as a conductor. Harsányi was a prolific composer of chamber music, solo piano works, and songs, as well as opera and ballet.

Hungarian-born pianist, composer, conductor, and musicologist Tibor Harsányi was part of the lively Paris musical scene from 1923. He was a student of Kodály in Budapest, then travelled around Europe as a performer, settling briefly in Holland, where he worked as a conductor. Harsányi was a prolific composer of chamber music, solo piano works, and songs, as well as opera and ballet.  The composer and musicologist Yulian Grigor’yevich Krein was son of Grigory Abramovich Krein. He studied composition with Dukas at the Ecole Normale in Paris, graduating in 1932, and lived in Moscow from 1934. His compositions developed under the influence of French music, but he also drew upon nineteenth-century Russian tradition and on the innovations of Skryabin. As a result his music is complex and many-sided, its lyricism clearly expressed in melodic breadth and colourful harmony. The French connection is most evident in his orchestration, while the chamber pieces are more Romantic in style. A prolific composer and a noted musicologist, he also appeared frequently as a pianist.

The composer and musicologist Yulian Grigor’yevich Krein was son of Grigory Abramovich Krein. He studied composition with Dukas at the Ecole Normale in Paris, graduating in 1932, and lived in Moscow from 1934. His compositions developed under the influence of French music, but he also drew upon nineteenth-century Russian tradition and on the innovations of Skryabin. As a result his music is complex and many-sided, its lyricism clearly expressed in melodic breadth and colourful harmony. The French connection is most evident in his orchestration, while the chamber pieces are more Romantic in style. A prolific composer and a noted musicologist, he also appeared frequently as a pianist.  Simon (Szymon) Laks had formerly worked as violin accompanist for silent films, and he had also some jazz-influenced compositions to his name, particularly a (now lost) Blues symphoniques – Jazz Fantasy for orchestra and saxophone (1928), a Sonate pour violoncelle et piano (1932) and a piano Blues, undated, but most probably from around the same period.

Simon (Szymon) Laks had formerly worked as violin accompanist for silent films, and he had also some jazz-influenced compositions to his name, particularly a (now lost) Blues symphoniques – Jazz Fantasy for orchestra and saxophone (1928), a Sonate pour violoncelle et piano (1932) and a piano Blues, undated, but most probably from around the same period.  Mihovil Logar was a Serbian composer (born in Rijeka) who had studied in Prague with Karel Boleslav Jirák and Josef Suk. The so-called Prague Generation of Serbian composers, in opposition to the old National School, was more cosmopolitan. There is no wonder why they readily took inspiration from dances of the New World, given the lineage at the Prague conservatory which, through Suk and Vítězslav Novák, went back to Dvořák. Logar’s piano output consists mostly of concise miniatures of a post-impressionist quality, written mostly around the mid-Thirties.

Mihovil Logar was a Serbian composer (born in Rijeka) who had studied in Prague with Karel Boleslav Jirák and Josef Suk. The so-called Prague Generation of Serbian composers, in opposition to the old National School, was more cosmopolitan. There is no wonder why they readily took inspiration from dances of the New World, given the lineage at the Prague conservatory which, through Suk and Vítězslav Novák, went back to Dvořák. Logar’s piano output consists mostly of concise miniatures of a post-impressionist quality, written mostly around the mid-Thirties.  Dora Pejačević was born in Budapest and grew up in her family’s palace in Našice, Slavonia. She studied in Dresden with Percy Sherwood and in Munich with Walter Courvoisier. Her output embraces songs, a piano concerto and a symphony. Most of her works feature the piano.

Dora Pejačević was born in Budapest and grew up in her family’s palace in Našice, Slavonia. She studied in Dresden with Percy Sherwood and in Munich with Walter Courvoisier. Her output embraces songs, a piano concerto and a symphony. Most of her works feature the piano.  Mischa Spoliansky was born into a Jewish musical family in Białystok (then part of the Russian Empire) and very early became a well-known figure in Berlin cafes and nightclubs, being – among others – the house composer and pianist at the well-known Schall und Rauch cabaret. In order to keep up with the times, like all cabaret musicians of this era, Spoliansky produced extraordinary musical examples of the new dances almost simultaneously with their American or English models. One example is his Jimmy Shimmy, composed as early as 1921, whose rhythmic pattern of dotted notes is constantly suspended by three marcato chords where the dancer, with his body still, could shimmy, i.e. move her/his shoulders alternately back and forth.

Mischa Spoliansky was born into a Jewish musical family in Białystok (then part of the Russian Empire) and very early became a well-known figure in Berlin cafes and nightclubs, being – among others – the house composer and pianist at the well-known Schall und Rauch cabaret. In order to keep up with the times, like all cabaret musicians of this era, Spoliansky produced extraordinary musical examples of the new dances almost simultaneously with their American or English models. One example is his Jimmy Shimmy, composed as early as 1921, whose rhythmic pattern of dotted notes is constantly suspended by three marcato chords where the dancer, with his body still, could shimmy, i.e. move her/his shoulders alternately back and forth.  Few composers in the twentieth century have such an exceptionally far-ranging career as Alexandre Tansman. Born in Poland in 1897 at Łódź, also the birthplace of his friend, the pianist Arthur Rubinstein, Tansman studied at the conservatory there and in Warsaw. He had as a fellow student the famous conductor and composer Paul Kletzki, who, as a violinist, took part in the first performance of Tansman’s now lost Piano Trio No. 1 and later conducted also in Paris his Fifth Symphony [Marco Polo 8.223379]. After winning in 1919 the three first prizes in the national composition competition organized in the newly established Polish Republic, Tansman settled in Paris, where he had the support and encouragement of Ravel and Roussel.

Few composers in the twentieth century have such an exceptionally far-ranging career as Alexandre Tansman. Born in Poland in 1897 at Łódź, also the birthplace of his friend, the pianist Arthur Rubinstein, Tansman studied at the conservatory there and in Warsaw. He had as a fellow student the famous conductor and composer Paul Kletzki, who, as a violinist, took part in the first performance of Tansman’s now lost Piano Trio No. 1 and later conducted also in Paris his Fifth Symphony [Marco Polo 8.223379]. After winning in 1919 the three first prizes in the national composition competition organized in the newly established Polish Republic, Tansman settled in Paris, where he had the support and encouragement of Ravel and Roussel.  Born in Ukraine, the composer and pianist Dimitri Tiomkin studied in St Petersburg with Blumenfeld and Glazunov, and with Busoni in Berlin, first embarking on a career as a concert pianist. In 1922 he settled in Paris but in 1929 moved with his choreographer wife to Hollywood, where he turned his attention to composition, first with scores for ballet films. After writing the music for the film Lost Horizon in 1937, he began a busy career as a film composer. In 1968 he moved to London, where he spent the last decade of his life.

Born in Ukraine, the composer and pianist Dimitri Tiomkin studied in St Petersburg with Blumenfeld and Glazunov, and with Busoni in Berlin, first embarking on a career as a concert pianist. In 1922 he settled in Paris but in 1929 moved with his choreographer wife to Hollywood, where he turned his attention to composition, first with scores for ballet films. After writing the music for the film Lost Horizon in 1937, he began a busy career as a film composer. In 1968 he moved to London, where he spent the last decade of his life.  Born in Bátaszék, Hungary, in 1894, Zádor demonstrated an early affinity for music (exhibiting great keyboard virtuosity) and at the age of sixteen went to study with Richard Heuberger in Vienna. A year later he moved to Leipzig, where he was a pupil of Max Reger. After completing his doctoral degree at the University of Münster, he returned to Vienna, where he taught at the New Vienna Conservatory through the 1920s. While there, he composed (among other works) a symphony and two operas (both produced by the Budapest Royal Opera). He left the conservatory in 1928 to devote himself full-time to composition and never ceased writing music until his death in 1977. His final catalogue comprised numerous works for orchestra (including four symphonies), several operas, chamber music, piano pieces, choral works, songs and various concertos for what he liked to call “underprivileged” instruments—including trombone, cimbalom, double bass and accordion.

Born in Bátaszék, Hungary, in 1894, Zádor demonstrated an early affinity for music (exhibiting great keyboard virtuosity) and at the age of sixteen went to study with Richard Heuberger in Vienna. A year later he moved to Leipzig, where he was a pupil of Max Reger. After completing his doctoral degree at the University of Münster, he returned to Vienna, where he taught at the New Vienna Conservatory through the 1920s. While there, he composed (among other works) a symphony and two operas (both produced by the Budapest Royal Opera). He left the conservatory in 1928 to devote himself full-time to composition and never ceased writing music until his death in 1977. His final catalogue comprised numerous works for orchestra (including four symphonies), several operas, chamber music, piano pieces, choral works, songs and various concertos for what he liked to call “underprivileged” instruments—including trombone, cimbalom, double bass and accordion. Reviews

“The pianist strikes exactly the right balance between hard rhythm and the more often than expected soft cantabile, with which he lends the supposedly “roaring” 1920s a reflective and meditative note. …A whole musical epoch opens up.” – Piano News

“...find some cheer in the third recording from the pianist Gottlieb Wallisch’s “20th Century Foxtrots” project. Past editions surprised and delighted in equal measure; this latest album on the Grand Piano label extends the streak.” – The New York Times

“This is another super release. I am sure this would have large appeal to anyone who enjoys this style of music and to pianists looking for unusual repertoire. I must now find the other volumes in the series. ” – Lark Reviews

Grand Piano has gained a reputation for producing high quality recordings of rare keyboard gems. Dedicated to the exploration of undiscovered piano repertoire, the label specialises in complete cycles of piano works by many lesser-known composers, whose output might otherwise have remained unknown and unrecorded.

Grand Piano has gained a reputation for producing high quality recordings of rare keyboard gems. Dedicated to the exploration of undiscovered piano repertoire, the label specialises in complete cycles of piano works by many lesser-known composers, whose output might otherwise have remained unknown and unrecorded.