About this Release

- Emma Bianchini

- Marco Enrico Bossi

- Charles Camilleri

- Franco Casavola

- Alfredo Casella

- Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco

- Victor De Sabata

- Ettore Desderi

- Anis Fuleihan

- Alfredo Gattari

- António Tomás de Lima

- Josep Martí i Cristià

- Federico Mompou

- Virgilio Mortari

- Giacomo Puccini

- Pedro F. Ribeiro d'Almeida

- Theophrastus Sakellaridis

- Domenico Savino

- Nikos Skalkottas

- Clifton Worsley

“The quest for relevant pieces to form a Southern European Foxtrot-album was a wonderful challenge! Including Italy, which offers the widest variety of styles and directions within early Jazz-influenced music, I am happy to present piano music from no less than 6 different countries. Well-known names like Mompou (with his early Foxtrot and Tango) and Casella stand out but then there are also composers with a truly mediterranean spirit from Malta, Cyprus or Greece. I found particular pleasure in Skalkottas’ substantial Shimmy Tempo, written in Berlin in 1924, which feels like an adequate musical description of the German capital’s craziness and bombast at that time. Introducing the “new” dances to kids was seemingly important to several composers from the South – the sets of children’s pieces offered by Bianchini or de Lima get to the core of the new rhythms on smallest scale. Here is Volume 6 of “20th Century Foxtrots” – a soulful and sunny album!” — Gottlieb Wallisch

20TH CENTURY FOXTROTS • 6

Southern Europe

- Gottlieb Wallisch, piano

This sixth volume of Gottlieb Wallisch’s acclaimed 20th Century Foxtrots series takes us to Southern Europe, with composers in Italy, Spain and other Mediterranean countries becoming caught up in the jazz craze that swept through dance and concert halls by the 1920s. International influences blend with regional character and famous names jostle with new discoveries, all of whose contributions create a joyous mix of exuberant theatricality, evocative elegance and colourful blues.

Tracklist

|

Casavola, Franco

|

|

1

Tango Viola da Cabaret Epilettico (1925) (00:02:55)

|

|

Gattari, Alfredo

|

|

2

2 Novelty Piano Solos: No. 2. Chopin's Charleston Dream () (00:02:24)

|

|

Bossi, Marco Enrico

|

|

3

2 Valzer, Op. 221: No. 2. Venus Valse, Boston-Valse (1921) (00:03:41)

|

|

De Sabata, Victor

|

|

4

Principe, Fox-Trot () (00:02:24)

|

|

Puccini, Giacomo

|

|

5

Piccolo Tango (1907) (00:01:58)

|

|

Casella, Alfredo

|

|

6

Cocktail's Dance (1918) (00:01:44)

|

|

7

9 Pezzi, Op. 24: No. 8. In Modo di Tango (1914) (00:03:54)

|

|

Desderi, Ettore

|

|

Preludio, Corale e Fuga in modo sincopato (1934) (00:05:00 )

|

|

8

Preludio (00:01:15)

|

|

9

Corale (00:02:25)

|

|

10

Fuga (00:01:37)

|

|

Castelnuovo-Tedesco, Mario

|

|

Media Difficoltà (1931) (00:12:00 )

|

|

11

No. 3. Tango (00:02:56)

|

|

12

No. 4. Fox-Trot (00:02:56)

|

|

Bianchini, Emma

|

|

Danze della mia bambola, Op. 8 () (00:05:00 )

|

|

13

No. 2. Hésitation (00:01:57)

|

|

14

No. 3. One-Step (00:00:50)

|

|

Danze della mia bambola, Op. 9 () (00:04:00 )

|

|

15

No. 2. Tango (00:01:21)

|

|

16

No. 3. Charleston (00:00:54)

|

|

Mortari, Virgilio

|

|

17

Fox-Trot del Teatro della Sorpresa (1921) (00:02:19)

|

|

Savino, Domenico

|

|

18

Arabesque in Blue (1928) (00:03:25)

|

|

Fuleihan, Anis

|

|

19

From the Aegean: II. Tango (1946) (00:01:29)

|

|

Skalkottas, Nikos

|

|

20

Suite for Piano: III. Shimmy tempo (1924) (fragment) (1924) (00:04:26)

|

|

Sakellaridis, Theophrastus

|

|

21

To Please Her Husband: Foxtrot-Schimmy (1922) (00:01:51)

|

|

Camilleri, Charles

|

|

Piano Études, Book 3, "The Picasso Set" () (00:12:00 )

|

|

22

I. Foxtrot (00:00:52)

|

|

23

V. Blues (00:02:36)

|

|

Martí i Cristià, Josep

|

|

24

The Joyous American: Rag-time (version for piano) () (00:02:17)

|

|

Worsley, Clifton

|

|

25

Five O'Clock Tea, Fox Trot () (00:01:17)

|

|

26

Triste Illusion, Valse triple Boston () (00:03:41)

|

|

Mompou, Federico

|

|

27

Fox-Trot (1916) (1916) (00:02:43)

|

|

28

Tango (1919) (1919) (00:03:38)

|

|

29

Ballet: V. Temps de blues (1949) (00:00:49)

|

|

Lima, António Tomás de

|

|

30

Album infantil, Series 3: No. 4. O Cuco bailarino, One-Step () (00:01:02)

|

|

Album infantil, Series 1 () (00:06:00 )

|

|

31

No. 2. Buffooning, Fox-Trot (00:01:03)

|

|

32

No. 3. Good-bye, One-Step (00:00:58)

|

|

Ribeiro d'Almeida, Pedro F.

|

|

33

Arraial, One-Step sobre motivos do fado () (00:01:01)

|

The Artist(s)

Born in Vienna, Gottlieb Wallisch first appeared on the concert platform when he was seven years old, and at the age of twelve made his debut in the Golden Hall of the Vienna Musikverein. A concert directed by Yehudi Menuhin in 1996 launched Wallisch’s international career: accompanied by the Sinfonia Varsovia, the seventeen-year-old pianist performed Beethoven’s ‘Emperor’ Concerto.

Since then Wallisch has received invitations to the world’s most prestigious concert halls and festivals including Carnegie Hall in New York, Wigmore Hall in London, the Cologne Philharmonie, the Tonhalle Zurich, the NCPA in Beijing, the Ruhr Piano Festival, the Beethovenfest in Bonn, the Festivals of Lucerne and Salzburg, December Nights in Moscow, and the Singapore Arts Festival. Conductors with whom he has performed as a soloist include Giuseppe Sinopoli, Sir Neville Marriner, Dennis Russell Davies, Kirill Petrenko, Louis Langrée, Lawrence Foster, Christopher Hogwood, Martin Haselböck and Bruno Weil.

Orchestras he has performed with include the Vienna Philharmonic and Vienna Symphony Orchestras, the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, the Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra, the Frankfurt Radio Symphony, the Festival Strings Lucerne, the Franz Liszt Chamber Orchestra in Budapest, the Musica Angelica Baroque Orchestra in Los Angeles, and the Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra.

Born in Vienna, Gottlieb Wallisch first appeared on the concert platform when he was seven years old, and at the age of twelve made his debut in the Golden Hall of the Vienna Musikverein. A concert directed by Yehudi Menuhin in 1996 launched Wallisch’s international career: accompanied by the Sinfonia Varsovia, the seventeen-year-old pianist performed Beethoven’s ‘Emperor’ Concerto.

Since then Wallisch has received invitations to the world’s most prestigious concert halls and festivals including Carnegie Hall in New York, Wigmore Hall in London, the Cologne Philharmonie, the Tonhalle Zurich, the NCPA in Beijing, the Ruhr Piano Festival, the Beethovenfest in Bonn, the Festivals of Lucerne and Salzburg, December Nights in Moscow, and the Singapore Arts Festival. Conductors with whom he has performed as a soloist include Giuseppe Sinopoli, Sir Neville Marriner, Dennis Russell Davies, Kirill Petrenko, Louis Langrée, Lawrence Foster, Christopher Hogwood, Martin Haselböck and Bruno Weil.

Orchestras he has performed with include the Vienna Philharmonic and Vienna Symphony Orchestras, the Royal Liverpool Philharmonic, the Gustav Mahler Youth Orchestra, the Frankfurt Radio Symphony, the Festival Strings Lucerne, the Franz Liszt Chamber Orchestra in Budapest, the Musica Angelica Baroque Orchestra in Los Angeles, and the Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra. The Composer(s)

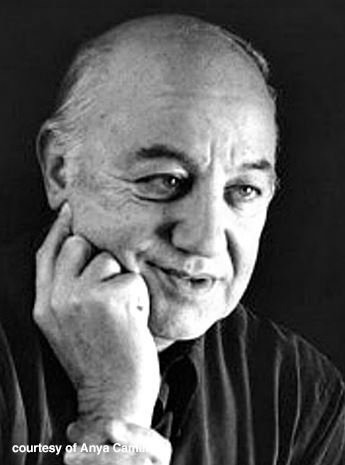

Charles Camilleri was born in Hamrun, Malta, in 1931. He showed early promise as an accordionist and pianist and started composing at the age of eleven. By the end of his teens he had written a number of compositions inspired by Maltese traditional music and, particularly, by the local style of folk singing known as għana. When Camilleri was eighteen, he emigrated to Australia and eventually moved to London where he earned his living as a successful light-music arranger, performer, composer and conductor, assisting Sir Malcolm Arnold on the Oscar-winning soundtrack of The Bridge on the River Kwai. In 1958 Camilleri left London for New York and then Canada, where he studied composition whilst working as resident conductor for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. He would eventually describe these “electrifying” years as amongst the most exciting of his life. They certainly gave him the confidence to dedicate himself to composition, which he did on his return to London in 1965. The following years brought him ever-increasing critical acclaim and prestigious collaborations. 1977 saw Camilleri’s appointment as Professor of Composition at the Royal Conservatory of Music, Toronto. Camilleri also gave lectures at Buffalo State University, a hotbed of musical modernism, where he met experimental composers such as Carter, Feldman and Cage. Their influence took root in a number of works of this period including the Organ Concerto (1981).

Charles Camilleri was born in Hamrun, Malta, in 1931. He showed early promise as an accordionist and pianist and started composing at the age of eleven. By the end of his teens he had written a number of compositions inspired by Maltese traditional music and, particularly, by the local style of folk singing known as għana. When Camilleri was eighteen, he emigrated to Australia and eventually moved to London where he earned his living as a successful light-music arranger, performer, composer and conductor, assisting Sir Malcolm Arnold on the Oscar-winning soundtrack of The Bridge on the River Kwai. In 1958 Camilleri left London for New York and then Canada, where he studied composition whilst working as resident conductor for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. He would eventually describe these “electrifying” years as amongst the most exciting of his life. They certainly gave him the confidence to dedicate himself to composition, which he did on his return to London in 1965. The following years brought him ever-increasing critical acclaim and prestigious collaborations. 1977 saw Camilleri’s appointment as Professor of Composition at the Royal Conservatory of Music, Toronto. Camilleri also gave lectures at Buffalo State University, a hotbed of musical modernism, where he met experimental composers such as Carter, Feldman and Cage. Their influence took root in a number of works of this period including the Organ Concerto (1981).  A composer and pianist, Castelnuovo-Tedesco was born in Florence into an Italian Jewish family. In 1939 he moved to the United States, where, in common with other European composers in exile, he turned his hand to film music, providing scores for some 250 films. He died in Los Angeles in 1968.

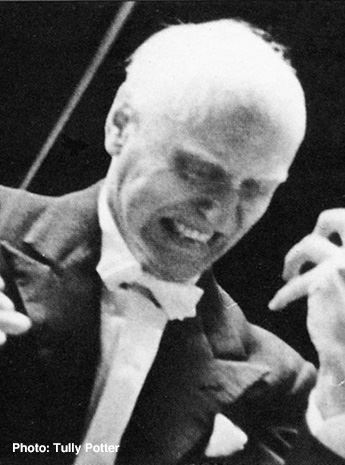

A composer and pianist, Castelnuovo-Tedesco was born in Florence into an Italian Jewish family. In 1939 he moved to the United States, where, in common with other European composers in exile, he turned his hand to film music, providing scores for some 250 films. He died in Los Angeles in 1968.  Victor de Sabata was born into a musical family: his father was a singing teacher and may have acted at some point as a chorusmaster for La Scala, Milan. Recognising Victor’s precocious musical talent, the family moved to Milan when he was eleven, and here he entered the Conservatory, studying violin, piano and composition and graduating in these subjects cum laude when he was eighteen. His music was swiftly taken up by conductors such as Tullio Serafin, at this time musical director at La Scala in succession to Toscanini, and Walter Damrosch, the conductor of the New York Symphony Orchestra. At the age of twenty-four, de Sabata was commissioned to compose an opera for La Scala: Il macigno was produced there in 1917. (de Sabata subsequently revised this work and it was re-presented at Turin under the title Driada in 1935.) Henceforth he was to pursue a twin career as a virtuoso conductor and for some time as a composer.

Victor de Sabata was born into a musical family: his father was a singing teacher and may have acted at some point as a chorusmaster for La Scala, Milan. Recognising Victor’s precocious musical talent, the family moved to Milan when he was eleven, and here he entered the Conservatory, studying violin, piano and composition and graduating in these subjects cum laude when he was eighteen. His music was swiftly taken up by conductors such as Tullio Serafin, at this time musical director at La Scala in succession to Toscanini, and Walter Damrosch, the conductor of the New York Symphony Orchestra. At the age of twenty-four, de Sabata was commissioned to compose an opera for La Scala: Il macigno was produced there in 1917. (de Sabata subsequently revised this work and it was re-presented at Turin under the title Driada in 1935.) Henceforth he was to pursue a twin career as a virtuoso conductor and for some time as a composer.  Those who know Ettore Desderi mainly for the austere sacred works in the late-Romantic vein for which he became famous might be surprised to learn that he also managed to channel his liking for jazz. His Preludio, Corale e Fuga in modo sincopato shows how Baroque and Classical forms sound when subjected to syncopation. The work begins originally, with a perpetuum mobile-like prelude. This is followed by a chorale with hints of the blues, before an elaborate closing fugue comes close to anticipating elements of free jazz which, historically speaking, didn’t develop until much later.

Those who know Ettore Desderi mainly for the austere sacred works in the late-Romantic vein for which he became famous might be surprised to learn that he also managed to channel his liking for jazz. His Preludio, Corale e Fuga in modo sincopato shows how Baroque and Classical forms sound when subjected to syncopation. The work begins originally, with a perpetuum mobile-like prelude. This is followed by a chorale with hints of the blues, before an elaborate closing fugue comes close to anticipating elements of free jazz which, historically speaking, didn’t develop until much later.  Anis Fuleihan made an intensive study of Middle Eastern traditional music as early as the 1920s. Inasmuch as he was director of the Beirut Conservatory from 1953 to 1960, and conductor of Beirut’s orchestra during the same period, Fuleihan is one of the founding fathers of Lebanese symphonic music. His orchestral works were premièred by the likes of John Barbirolli and Leopold Stokowski, and he himself frequently conducted the New York Philharmonic. After teaching at Indiana University for many years, Fuleihan held appointments first in Beirut and later in Tunisia, where he founded the Orchestre Classique de Tunis in 1962. Not only his biography, but also his music gives the impression that he was a focussed and vigorous cosmopolitan.

Anis Fuleihan made an intensive study of Middle Eastern traditional music as early as the 1920s. Inasmuch as he was director of the Beirut Conservatory from 1953 to 1960, and conductor of Beirut’s orchestra during the same period, Fuleihan is one of the founding fathers of Lebanese symphonic music. His orchestral works were premièred by the likes of John Barbirolli and Leopold Stokowski, and he himself frequently conducted the New York Philharmonic. After teaching at Indiana University for many years, Fuleihan held appointments first in Beirut and later in Tunisia, where he founded the Orchestre Classique de Tunis in 1962. Not only his biography, but also his music gives the impression that he was a focussed and vigorous cosmopolitan.  António Tomás de Lima – born in Lisbon and not to be confused with his equally prolific pianist and composer son Eurico – pays homage to the dance music of the 1920s in some of his children’s pieces. There is a dancing cuckoo (O cuco bailarino. One-Step), some joyously innocuous clowning (Buffooning. Fox-Trot) and a speedy farewell (Good-bye. One-Step).

António Tomás de Lima – born in Lisbon and not to be confused with his equally prolific pianist and composer son Eurico – pays homage to the dance music of the 1920s in some of his children’s pieces. There is a dancing cuckoo (O cuco bailarino. One-Step), some joyously innocuous clowning (Buffooning. Fox-Trot) and a speedy farewell (Good-bye. One-Step).  Catalan by birth, Federico Mompou studied in his native Barcelona before moving to Paris, where, before and after the war, he spent over 20 years. His music, much of it for piano, is economical in means with something of the sparse texture familiar from Satie, another perceptible influence.

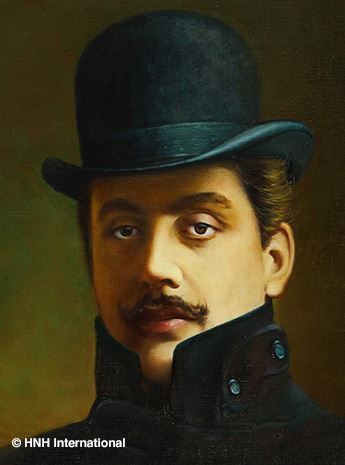

Catalan by birth, Federico Mompou studied in his native Barcelona before moving to Paris, where, before and after the war, he spent over 20 years. His music, much of it for piano, is economical in means with something of the sparse texture familiar from Satie, another perceptible influence.  Descended from a family of musicians, Puccini was the most important Italian opera composer in the generation after Verdi. He was born and educated in Lucca, later studying under Ponchielli at the Milan Conservatory. He began his career as a composer of opera with Le Villi, on the story familiar from Adam’s ballet Giselle, but first won significant success in 1893 with Manon Lescaut. A musical dramatist of considerable power, if sometimes lacking in depth, he wrote 12 operas in total, the last, Turandot, still unfinished at the time of his death in 1924.

Descended from a family of musicians, Puccini was the most important Italian opera composer in the generation after Verdi. He was born and educated in Lucca, later studying under Ponchielli at the Milan Conservatory. He began his career as a composer of opera with Le Villi, on the story familiar from Adam’s ballet Giselle, but first won significant success in 1893 with Manon Lescaut. A musical dramatist of considerable power, if sometimes lacking in depth, he wrote 12 operas in total, the last, Turandot, still unfinished at the time of his death in 1924.  Nikos Skalkottas is universally recognised as a leading member of the Second Viennese School and its most prominent Greek composer, who wrote atonal, twelve-tone, neo-Classical and tonal music. A brilliant violinist, Skalkottas moved to Berlin in 1921 at the age of 17 where he studied violin with Willy Hess and composition, staying there until his repatriation in 1933, never to leave Athens again. Although playing the violin in various ensembles and settings remained the main source of income throughout his life, by 1923 he had already turned his efforts to composition. Two of the leading composers with whom he studied were Kurt Weill and Arnold Schoenberg; in fact, the latter considered Skalkottas among his ‘most gifted students’.

Nikos Skalkottas is universally recognised as a leading member of the Second Viennese School and its most prominent Greek composer, who wrote atonal, twelve-tone, neo-Classical and tonal music. A brilliant violinist, Skalkottas moved to Berlin in 1921 at the age of 17 where he studied violin with Willy Hess and composition, staying there until his repatriation in 1933, never to leave Athens again. Although playing the violin in various ensembles and settings remained the main source of income throughout his life, by 1923 he had already turned his efforts to composition. Two of the leading composers with whom he studied were Kurt Weill and Arnold Schoenberg; in fact, the latter considered Skalkottas among his ‘most gifted students’. Reviews

“…I am loving Wallisch’s thrilling pianism, his energy and characterisation as well as his wonderful sense of adventure and passion for this repertoire…” – MusicWeb International

Grand Piano has gained a reputation for producing high quality recordings of rare keyboard gems. Dedicated to the exploration of undiscovered piano repertoire, the label specialises in complete cycles of piano works by many lesser-known composers, whose output might otherwise have remained unknown and unrecorded.

Grand Piano has gained a reputation for producing high quality recordings of rare keyboard gems. Dedicated to the exploration of undiscovered piano repertoire, the label specialises in complete cycles of piano works by many lesser-known composers, whose output might otherwise have remained unknown and unrecorded.